记录了学习《Programming Rust》笔记。

Chapter 3. Fundamental Types

- Rust有类型推断

- 函数可以是泛型的

Rust的类型

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| i8,i16,i32,i64,i128,u8,u16,u32,u64,u128 | |

| isize,usize | |

| f32,f64 | |

| bool | |

| char | |

| (char, u8, i32) | 元组 |

| () | |

struct S { x: f32, y:f32 } | 结构体 |

struct T (i32, char); | Tuple-like struct |

struct E; | Unit-like struct; has no fields |

enum Attend { OnTime, Late(u32) } | |

Box<Attend> | |

| &i32,&mut i32 | |

| String | |

| &str | |

| [f64; 4], [u8; 256] | |

Vec<f64> | |

| &[u8], &mut [u8] | |

| Option<&str> | |

| Result<u64, Error> | |

| &dyn Any, &mut dyn Read | |

| fn(&str) -> bool | |

| (Clousure types have no written form) | Clousure |

Fixed-Width Numerical Types

如果需要任意精度表示的一些数值,可以查看 num 包。

Integer Types

不像C和C++,Rust将字符看作是和数值不同的类型,一个 char 不是 u8,也不是 u32(尽管字符是32位长的)。

Rust要求数组的索引必须是 usize 类型的值。

在Rust整数可以带一个后缀来表示它们的类型,比如42u8。如果没有给整数指定具体的类型,Rust会将值存放在一个特定的类型中,传给函数期望的参数,比较另一个有别的特定类型的值,最后,如果有多个可能,而 i32是其中一个的话,就默认是 i32类型,否则就会报错。

前缀0x,0o和0b表示十六进制、八进制和二进制。

为了更清楚地表示很长的数字,还可以给数字加下划线,比如4_294_967_295。有前缀和后缀的数字依然可以加下划线。

尽管Rust中数字和字符是不同的类型,但是也提供了 字节字面量( byte literals),即用类字符字面量表示u8值:b'X'代表的ASCII编码的字符X,它是一个u8值。比如,由于字符A的ASCII编码是65,因此b'A'等价于65u8。字节字面量中只能出现在ASCII编码的字符。

特殊的ACSII编码的字符

| Character | Byte literal |

|---|---|

| 单引号 | b'\'' |

| 反斜杠 | b'\\' |

| 换行 | b'\n' |

| 回车 | b'\r' |

| 制表符 | b'\t' |

对于一些ASCII编码的字符可以用十六进制来表示,这样更容易阅读。比如b'\x1b'。

整数类型之间转换可以用 as 操作符。比如 10_i8 as u16。

整数的一些方法,参见 std::i32。

| |

看下面这段代码

| |

这里没有给出数值的类型,是不是默认 i32 呢?但其实会报错:

| |

为什么会这样子呢?因为Rust想要在调用一个类型自己的方法之前明确地知道一个值的整数类型。i32 的默认值仅适用于在所有方法调用都已解决后类型仍然不明确的情况,在这里就太晚了,因此会报错。换句话说,就是这里我要先调用 abs()方法,这个时候需要确定类型,还没等推断出默认类型,就已经报错了。解决方案:

| |

注意方法调用会发生在一元前缀操作符之前,所以处理负数的时候要当心。比如-4_i32.abs(),这里没有括号,会先调用函数4_i32.abs(),然后再取负号,最终结果为-4。

Checked, Wrapping, Saturating, and Overflowing Arithmetic

在Debug模式下,如果整数数值操作溢出,会报错。但是在发布模式构建的时候,会 wraps。

In a release build, the operation wraps around: it produces the value equivalent to the mathematically correct result modulo the range of the value. (In neither case is overflow undefined behavior, as it is in C and C++.)

上述是默认的,如果这不是你想要的,可以调用一些方法,主要有四类。

- Checked operations return an Option of the result: Some(v) if the mathematically correct result can be represented as a value of that type, or None if it cannot.

- Wrapping operations return the value equivalent to the mathematically correct result modulo the range of the value.

- Saturating operations return the representable value that is closest to the mathematically correct result. In other words, the result is “clamped” to the maximum and minimum values the type can represent.

- Overflowing operations return a tuple (result, overflowed), where result is what the wrapping version of the function would return, and overflowed is a bool indicating whether an overflow occurred.

| Operation | Name suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Addition | add | 100_i8.checked_add(27) == Some(127) |

| Subtraction | sub | 10_u8.checked_sub(11) == None |

| Multiplication | mul | 128_u8.saturating_mul(3) == 255 |

| Division | div | 64_u16.wrapping_div(8) == 8 |

| Remainder | rem | (-32768_i16).wrapping_rem(-1) == 0 |

| Negation | neg | (-128_i8).checked_neg() == None |

| Absolute value | abs | (-32768_i16).wrapping_abs() == -32768 |

| Exponentiation | pow | 3_u8.checked_pow(4) == Some(81) |

| Bitwise left shift | shl | 10_u32.wrapping_shl(34) == 40 |

| Bitwise right shift | shr | 40_u64.wrapping_shr(66) == 10 |

Floating-Point Types

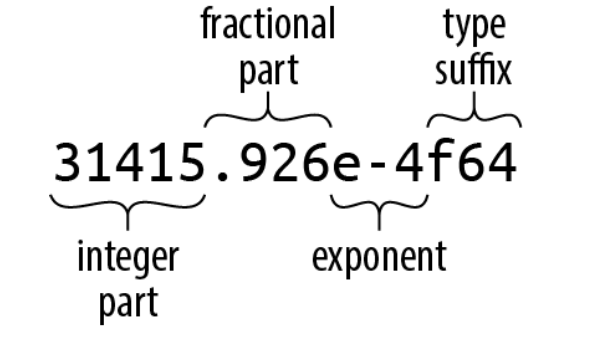

整数部分后的分数部分,指数或者类型后缀至少包含一个,来区别于整数字面量。5.整数部分之后只有一个小数点,也是一个有效的浮点数常数。

浮点数默认类型是 f64 。

为了类型推断的目的,Rust中整数和浮点数之间不会进行相互推断。

f32和f64都有一些特殊值,如 INFINITY,NEG_INFINITY,NAN(that not-a-number value),MIN和MAX。

std::f32::consts和std::f64::consts提供一些数学常量。

Rust是没有数值的隐式转换的,所以如果传入的参数类型和函数的参数类型不一致,这里不会发生隐式转换,因此会报错。想要转换只能显式地用 as 操作符。

The bool Type

在Rust中,bool类型的值为 true 和 false。

Rust中在要求一个Boolean值的上下文中是非常严格的。控制结构if和while要求条件必须是 bool 表达式, 短路逻辑操作符 && 和 || 也要求必须是 bool 表达式。必须 if x!= 0 { ... }这样写,而不能简单地写为 if x { ... }。

Rust可以用 as 操作符将 bool 值转换为数字,但是不能反过来将数值转换为 bool 值。

| |

虽然可以只有一位就表示 bool 值,但是Rust底层用一整个字节来存储 bool 值,这样的话就可以创建一个指针来指向它。

Characters

char 类型表示单个Unicode字符,占 32 位。

字符可以用十六进制来表示或者\u{}来表示。

- 如果字符编码在ASCII编码范围内,可以用十六进制。例如

'\xHH'。 - 也可以用

\u{}来表示任何的Unicode编码字符。例如'\u{HHHHHH}'。

字符必须在有效的 Unicode 码点范围内。

char 和其他类型之间没有隐式地转换。当然可以显式用 as 操作符将 char 类型转换成一个整数类型,如果类型小于32位,会进行截断。相反地,只有 u8 类型能用 as 操作符显式地转换为 char 类型。这一点也很自然,Rust要保证可靠,其他数值类型转换成 char 类型时,可能是无效的字符。不过std::char::from_u32可以将任何 u32 类型的值转换,返回的是 Option<char>。

char(primitive type)文档有相关的方法。

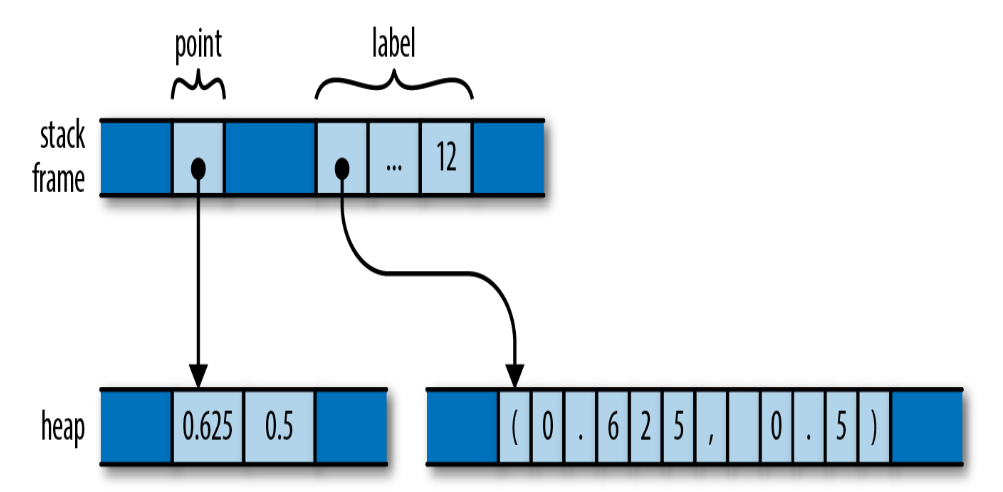

Tuples

元组可以将不同类型的值组合在一起,可以用在返回多个不同类型的值的函数中。

用 a.0可以来获取具体的元素。

元组的索引必须是常数,不可以是变量,比如t[i]或者t.i就是错误的。

可以用模式匹配得到元组对应的值。在指定变量值或者函数返回多个值时很有用。用元组来表示相关的变量是很清晰的,比如宽和高,可以用一个元组把它们放在一起,语义更加清晰。

unit type ()可以用于函数的返回类型,表示什么也不返回。

可以在元组的最后加上逗号,容易看出列表删除或添加了元素。如果是单个值,("lonely hearts",)相比 ("lonely hearts")更加清晰,可以判断是元组而不是括号表达式。

Pointer Types

References

&x 产生了对 x 的一个引用,用Rust的术语来说是向 x 借了一个引用。

在Rust中,引用始终不为空。Rust会跟踪值的所有权和生命周期,在编译时期会检查出悬垂指针,二次释放以及指针无效的错误。

- & T:不可变的共享引用

- &mut T:可变的独占引用

将不可变引用和可变引用看作单个读-写者和多个读者。

Boxes

用于堆分配的指针类型。

| |

Raw Pointers

- *const T

- *mut T

只能在 unsafe 块中对原始指针解引用。

Arrays, Vectors, and Slices

有三种类型表示内存中连续的一块数据。

[T; N]表示数组。数组的长度必须要在编译时期就确定。Vec<T>表示 T 类型的向量。动态分配的,元素存放在堆上。&[T]和&mut [T]称为 T 的共享切片或可变切片。可以把切片看作是一个胖指针,指向第一个元素,同时还包含可以访问到的元素的个数。

一些方法:

v.len()返回元素的个数。v[i]表示 v 的第 i 个元素,注意这里索引 i 必须是 usize 类型的。Rust总是会去检查 i 有没有在有效的范围内。

Arrays

直接用方括号生成数组,或者[T; N]生成数组,Rust不提供未初始化的数组。

数组的长度必须在编译时就确定,不可以用变量,比如[true; n] 这就是错误的。如果想在运行期间获得数组的长度,应该用向量。

在调用一些数组的方法时,Rust会隐式地将一个数组的引用转换为切片,这样可以直接在一个数组上使用任何切片的方法。

| |

关于这一点,官方文档是这样说的。

数组强制转换为

slices ([T]),因此可以在数组上调用 slice 方法。实际上,这提供了用于处理数组的大多数 API。 切片具有动态大小,并且不强制转换为数组。

Vectors

在堆上分配的容器。

可以用 vec!或者Vec::new()来生成新的 vector。

可以动态添加元素:

| |

可以用重复表达式来创建 vector:

| |

迭代器构造:

| |

和数组一样,向量也会在调用一些方法时隐式地转换为切片类型。

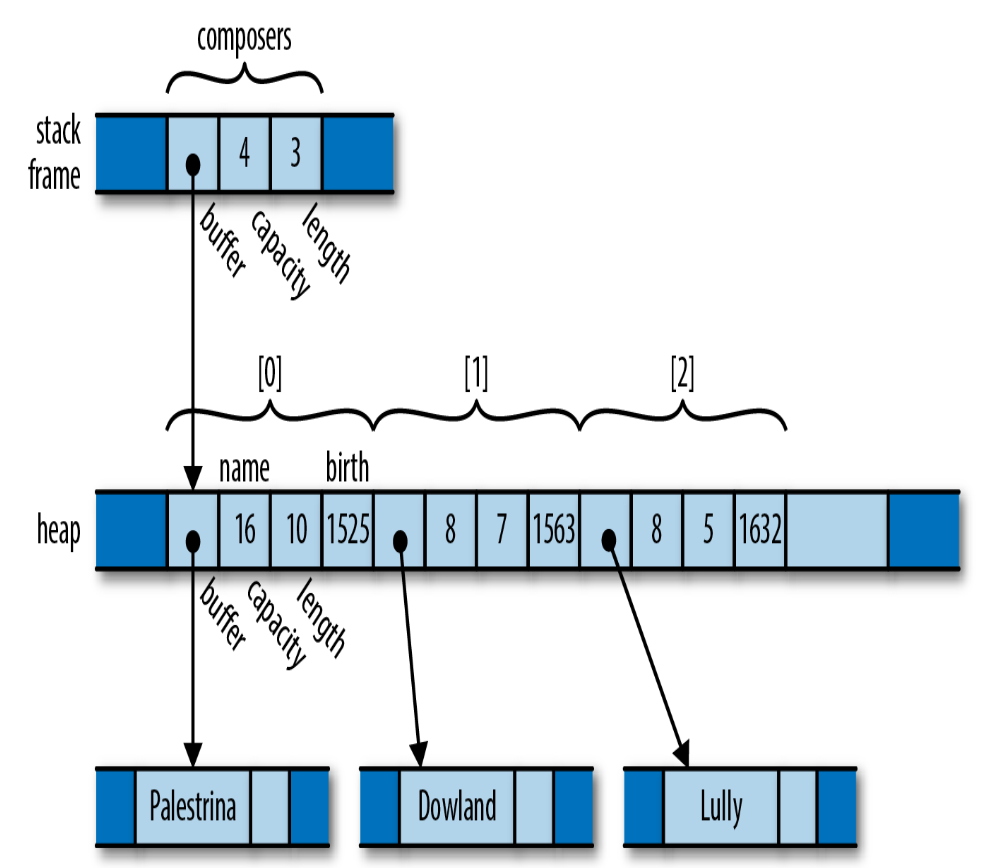

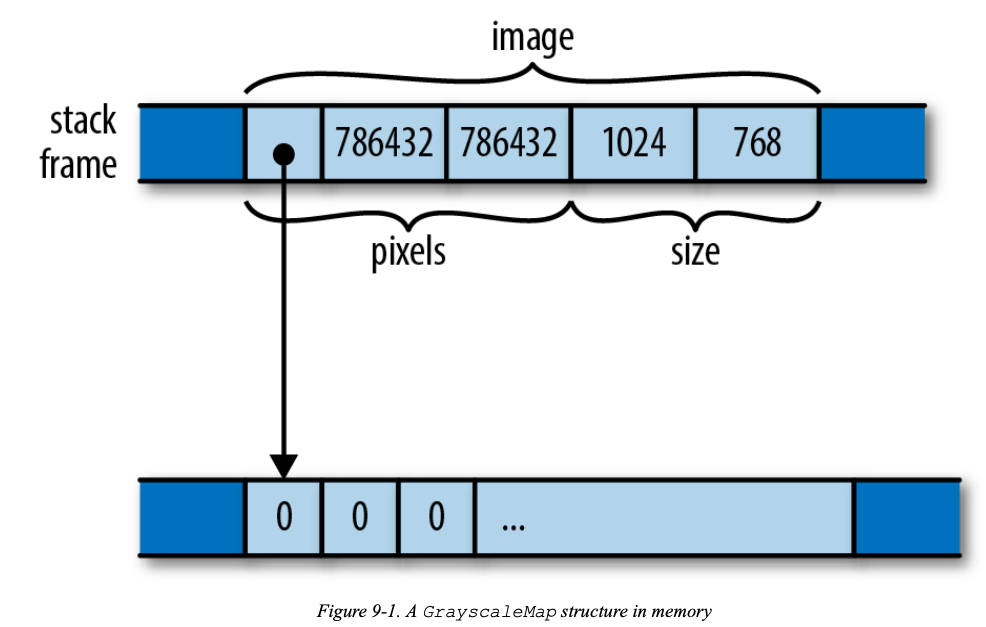

一个 Vec<T> 包含三个值:指向元素的堆 buffer 的指针,这个是被 Vec<T> 所创建和拥有的; buffer 中的容量;包含元素的个数,也就是长度。

知道向量的容量,可以用Vec::with_capacity来创建。提升效率,减少重新分配空间。

capacity方法返回向量不需要再分配时向量的容量。

一些方法:

- insert

- remove

- pop

可以用 for 在向量上进行迭代。

Slices

切片,直接指向引用的数据,看作一个胖指针,指向第一个元素,以及包含 len。

String Types

String Literals

字符串字面量在双引号内。

| |

Byte Strings

带有 b 前缀的是一个字节字面量。

| |

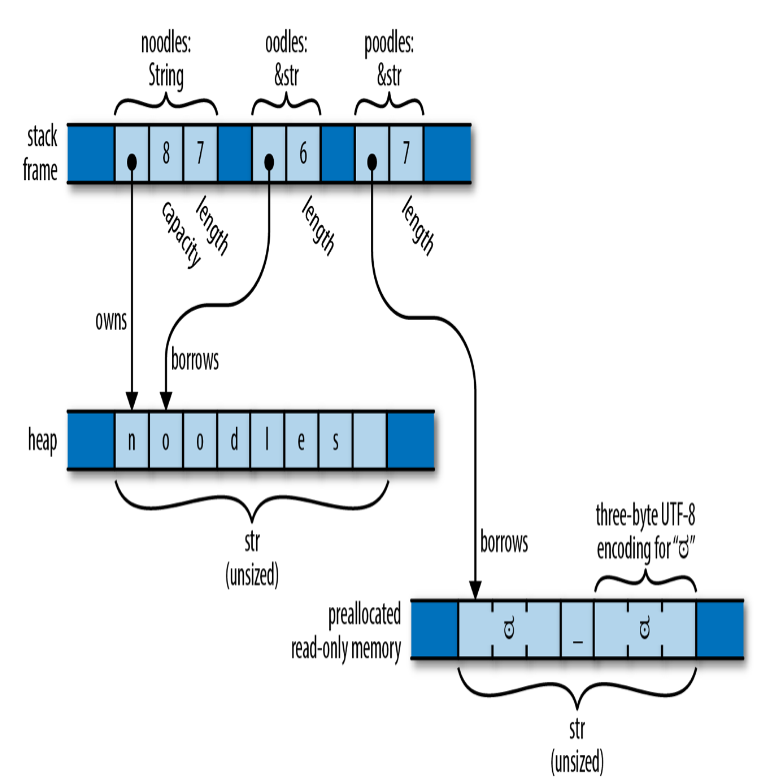

Strings in Memory

内存中以UTF-8编码存储。

| |

内存布局:

String

&str像&[T],而 String像Vec<T>。

创建 String:

| |

Using Strings

Strings support the == and != operators. Two strings are equal if they contain the same characters in the same order (regardless of whether they point to the same location in memory).

Other String-Like Types

- Stick to String and &str for Unicode text.

- When working with filenames, use std::path::PathBuf and &Path instead.

- When working with binary data that isn’t UTF-8 encoded at all, use

Vec<u8>and &[u8]. - When working with environment variable names and command-line arguments in the native form presented by the operating system, use OsString and &OsStr.

- When interoperating with C libraries that use null-terminated strings, use std::ffi::CString and &CStr.

Type Aliases

类型别名用 type :

| |

Chapter 4. Ownership and Moves

管理内存,想达到的效果:

- 当我们选择一个时间时,内存可以及时释放

- 内存释放后,不再有指针指向它

目前的内存管理方案:

- GC,垃圾回收。解决了悬垂指针的问题,但是会出现世界停时,也就是我们期望释放内存的时候,它还没有释放。

- 自己完全控制内存,比如C和C++。但是对程序员要求高,使用不当有时也会发生错误。

Rust是怎么解决这个问题的呢?秘密武器就是限制你的程序对指针的使用。给的这些限制会保证安全,但也不会丧失自由度。书中这样写道:

Rust’s radical wager, the claim on which it stakes its success and that forms the root of the language, is that even with these restrictions in place, you’ll find the language more than flexible enough for almost every task and that the benefits—the elimination of broad classes of memory management and concurrency bugs—will justify the adaptations you’ll need to make to your style. The authors of this book are bullish on Rust exactly because of our extensive experience with C and C++. For us, Rust’s deal is a no-brainer.

Ownership

在Rust中,所有权的概念是内建在语言中的,并且会通过编译器检查强制执行。每个值都有一个所有者,这个所有者决定它的生命周期。当所有者被释放时,它所拥有的值也会被释放。

| |

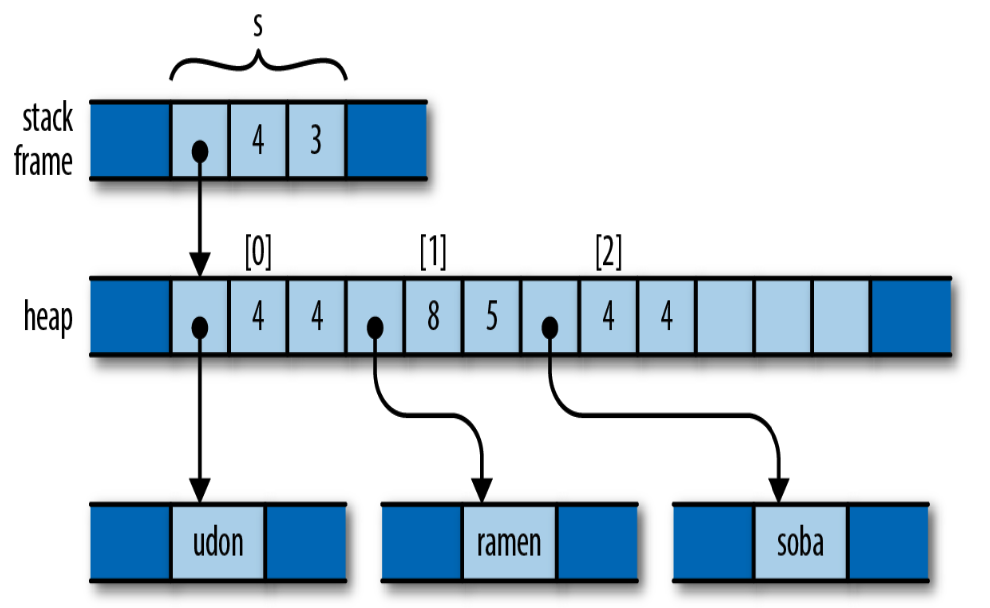

内存布局:

像变量会拥有它的值,结构体会拥有它们的字段,元组、数组以及向量会拥有它们的元素。

再看一个复杂的例子:

| |

内存布局:

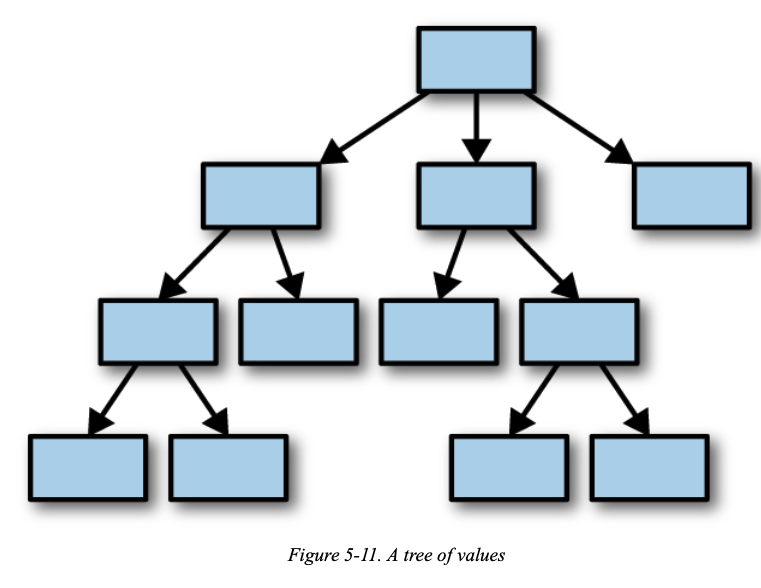

每个值都有一个单独的所有者,这个所有者很容易来决定什么时候 drop 它所拥有的值。但是一个单独的值可能会拥有很多其他的值,如上面这个例子中的向量 composers。所有者和它们所拥有的值会形成一个树。在每个树的根部是一个变量,当这个变量离开它的作用范围,整棵树也会跟着离开。

Rust通常不会显式地 drop 它的值,而是通过:离开变量的作用域,从向量中删除一个元素,或者其他的。

Rust怎么在这些严格的限制下实现灵活性呢?如下列出了一些方式:

- You can move values from one owner to another. This allows you to build, rearrange, and tear down the tree.

- Very simple types like integers, floating-point numbers, and characters are excused from the ownership rules. These are called Copy types.

- The standard library provides the reference-counted pointer types Rc and Arc, which allow values to have multiple owners, under some restrictions.

- You can “borrow a reference” to a value; references are non-owning pointers, with limited lifetimes.

Moves

In Rust, for most types, operations like assigning a value to a variable, passing it to a function, or returning it from a function don’t copy the value: they move it. The source relinquishes ownership of the value to the destination and becomes uninitialized; the destination now controls the value’s lifetime. Rust programs build up and tear down complex structures one value at a time, one move at a time.

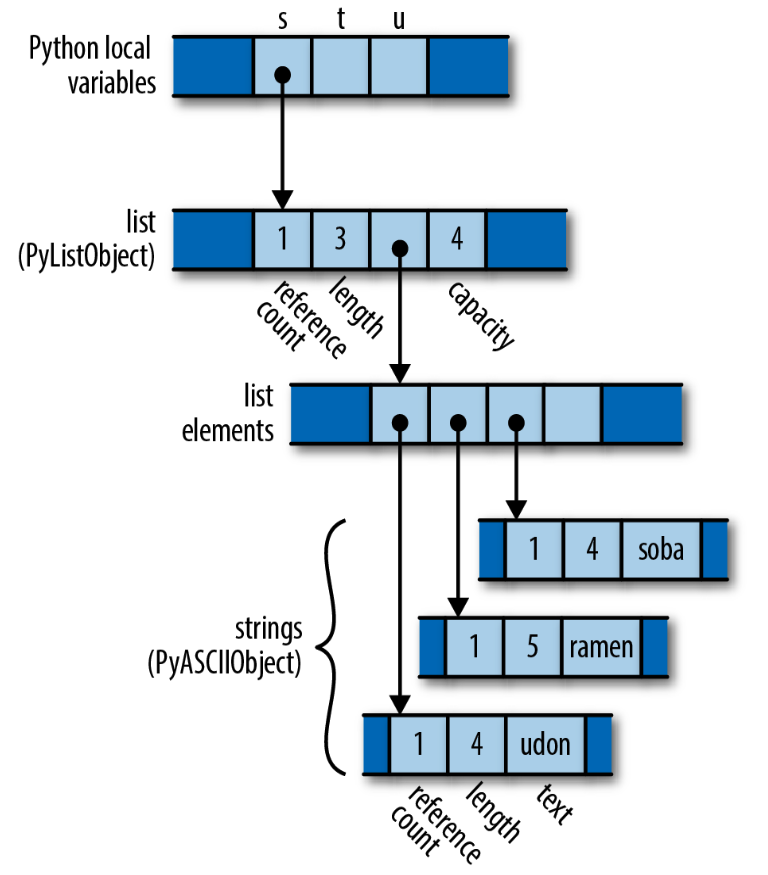

看看Python中的变量赋值。

| |

开始的内存布局:

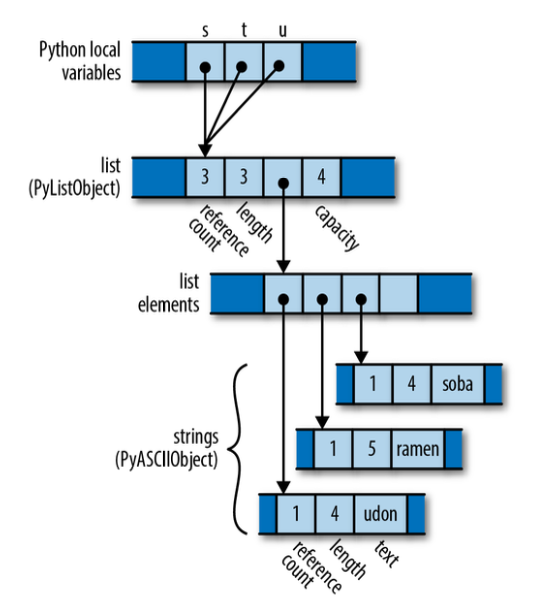

执行代码后的内存布局:

Python has copied the pointer from s into t and u and updated the list’s reference count to 3. Assignment in Python is cheap, but because it creates a new reference to the object, we must maintain reference counts to know when we can free the value.

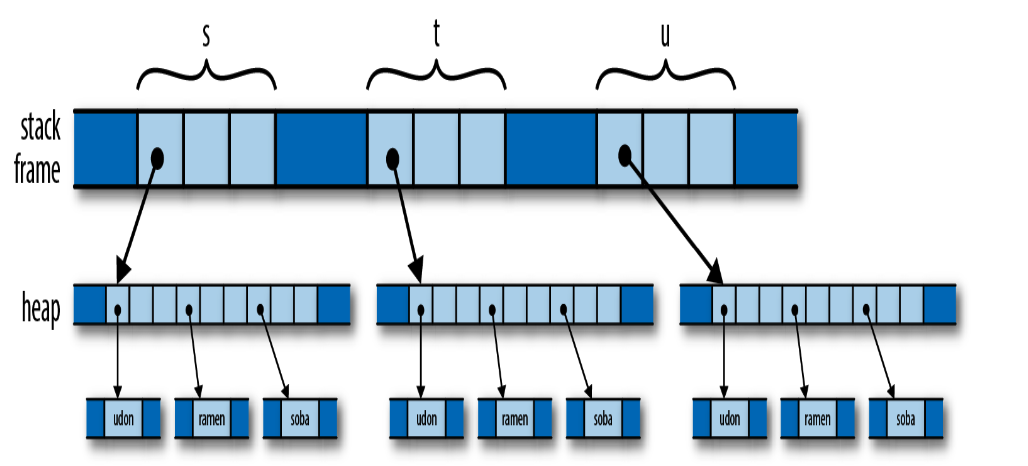

来看看C++中的实现:

| |

开始的内存布局

代码执行后的内存布局:

Depending on the values involved, assignment in C++ can consume unbounded amounts of memory and processor time. The advantage, however, is that it’s easy for the program to decide when to free all this memory: when the variables go out of scope, everything allocated here gets cleaned up automatically.

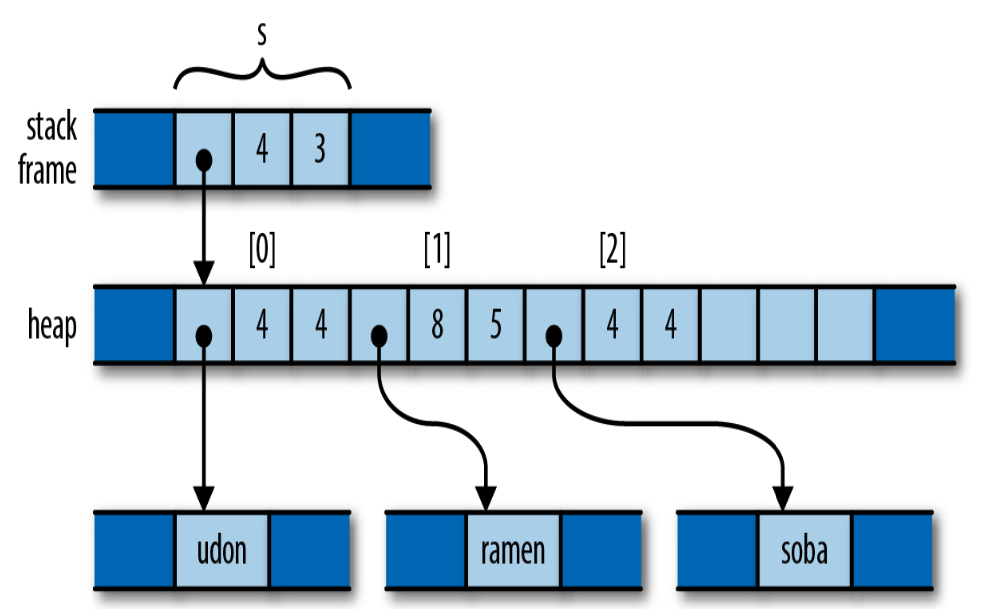

Rust中的实现:

| |

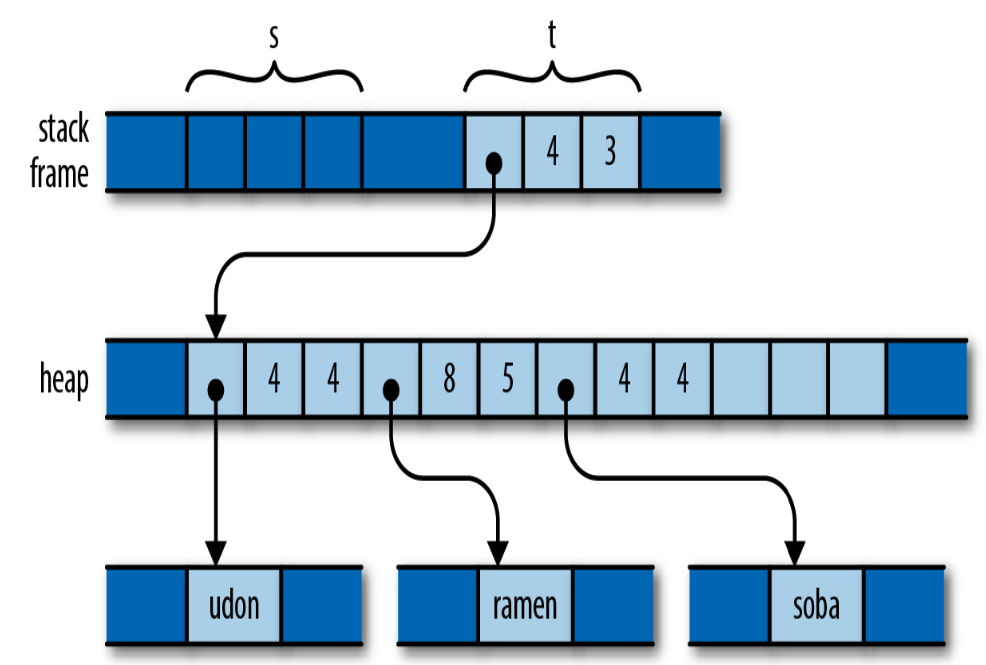

开始的内存分布:

在let t = s;之后,s 的所有权就 move 到 t 上了。

这时 s 变成未初始化状态,再执行 let u = s; 就会报错,因为使用了未初始化的变量。

Consider the consequences of Rust’s use of a move here. Like Python, the assignment is cheap: the program simply moves the three-word header of the vector from one spot to another. But like C++, ownership is always clear: the program doesn’t need reference counting or garbage collection to know when to free the vector elements and string contents.

如果想实现Python那样的引用计数,可以用 Rc 和 Arc,如果想实现C++那样的深拷贝,可以显式调用 clone() 方法。

More Operations That Move

move语义的发生:

- 给一个函数传递参数,会将所有权给参数

- 从函数返回一个值会将所有权给调用者

- 创建一个元组,会将值的所有权给元组

Moving values around like this may sound inefficient, but there are two things to keep in mind. First, the moves always apply to the value proper, not the heap storage they own. For vectors and strings, the value proper is the three-word header alone; the potentially large element arrays and text buffers sit where they are in the heap. Second, the Rust compiler’s code generation is good at “seeing through” all these moves; in practice, the machine code often stores the value directly where it belongs.

Moves and Control Flow

If it’s possible for a variable to have had its value moved away and it hasn’t definitely been given a new value since, it’s considered uninitialized.

Moves and Indexed Content

We’ve mentioned that a move leaves its source uninitialized, as the destination takes ownership of the value. But not every kind of value owner is prepared to become uninitialized.

| |

要将 vector 看作一个整体,这里不能单独将 v[2] move 出来。如果确实想拿出其中的元素,有下面一些方法:

| |

来看看循环

| |

这里在for循环中,v 的所有权给了for循环,v 就变成未初始化的状态,然后 for 循环分离每一个元素,将所有权给每一个。因为 s 有所有权,就可以在内部修改字符串了。

由于在循环中将 v 的所有权给了循环,因此后面就不能再使用 v 了,下面代码就会报错。

| |

如果想得到结构体中的元素值,可以调用 std::mem::replace方法,将原来的值用None来占位。

| |

Copy Types: The Exception to Moves

Assigning a value of a Copy type copies the value, rather than moving it. The source of the assignment remains initialized and usable, with the same value it had before. Passing Copy types to functions and constructors behaves similarly.

The standard Copy types include all the machine integer and floating-point numeric types, the char and bool types, and a few others. A tuple or fixed-size array of Copy types is itself a Copy type.

Only types for which a simple bit-for-bit copy suffices can be Copy. As a rule of thumb, any type that needs to do something special when a value is dropped cannot be Copy.

自定义的结构体或者枚举类型可以用属性宏实现 Copy trait。

| |

In Rust, every move is a byte-for-byte, shallow copy that leaves the source uninitialized. Copies are the same, except that the source remains initialized.

One of Rust’s principles is that costs should be apparent to the programmer. Basic operations must remain simple. Potentially expensive operations should be explicit, like the calls to clone in the earlier example that make deep copies of vectors and the strings they contain.

Rc and Arc: Shared Ownership

The Rc and Arc types are very similar; the only difference between them is that an Arc is safe to share between threads directly—the name Arc is short for atomic reference count—whereas a plain Rc uses faster non-thread-safe code to update its reference count.

前面的例子用Rust实现Python中引用计数的效果:

| |

内存布局:

Rust’s memory and thread-safety guarantees depend on ensuring that no value is ever simultaneously shared and mutable. Rust assumes the referent of an Rc pointer might in general be shared, so it must not be mutable.

However, Rust does provide ways to create mutable portions of otherwise immutable values; this is called interior mutability. 这可能造成循环引用。

想要用Rc避免循环引用。You can sometimes avoid creating cycles of Rc pointers by using weak pointers, std::rc::Weak, for some of the links instead.

Chapter 5. References

Rust also has non-owning pointer types called references, which have no effect on their referents’ lifetimes.

In fact, it’s rather the opposite: references must never outlive their referents. You must make it apparent in your code that no reference can possibly outlive the value it points to. To emphasize this, Rust refers to creating a reference to some value as borrowing the value: what you have borrowed, you must eventually return to its owner.

References to Values

A reference lets you access a value without affecting its ownership. References come in two kinds:

- A shared reference lets you read but not modify its referent. However, you can have as many shared references to a particular value at a time as you like. The expression

&eyields a shared reference to e’s value; if e has the type T, then &e has the type &T, pronounced “ref T.” Shared references are Copy. - If you have a mutable reference to a value, you may both read and modify the value. However, you may not have any other references of any sort to that value active at the same time. The expression &mut e yields a mutable reference to e’s value; you write its type as &mut T, which is pronounced “ref mute T.” Mutable references are not Copy.

| |

Iterating over a shared reference to a HashMap is defined to produce shared references to each entry’s key and value: artist has changed from a String to a &String, and works from a Vec<String> to a &Vec<String>.

The inner loop is changed similarly. Iterating over a shared reference to a vector is defined to produce shared references to its elements, so work is now a &String. No ownership changes hands anywhere in this function; it’s just passing around non-owning references.

When we pass a value to a function in a way that moves ownership of the value to the function, we say that we have passed it by value. If we instead pass the function a reference to the value, we say that we have passed the value by reference.

Working with References

Rust References Versus C++ References

In Rust, references are created explicitly with the & operator, and dereferenced explicitly with the * operator.

Since references are so widely used in Rust, the . operator implicitly dereferences its left operand, if needed.

| |

The println! macro used in the show function expands to code that uses the . operator.

The . operator can also implicitly borrow a reference to its left operand, if needed for a method call.

| |

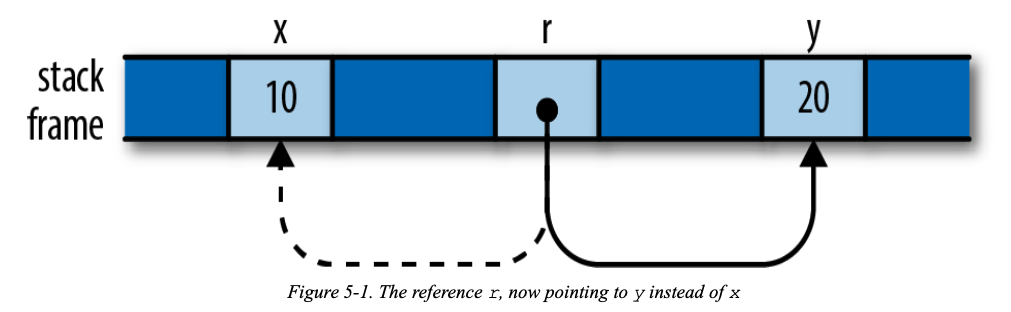

Assigning References

| |

The reference r initially points to x. But if b is true, the code points it at y instead.

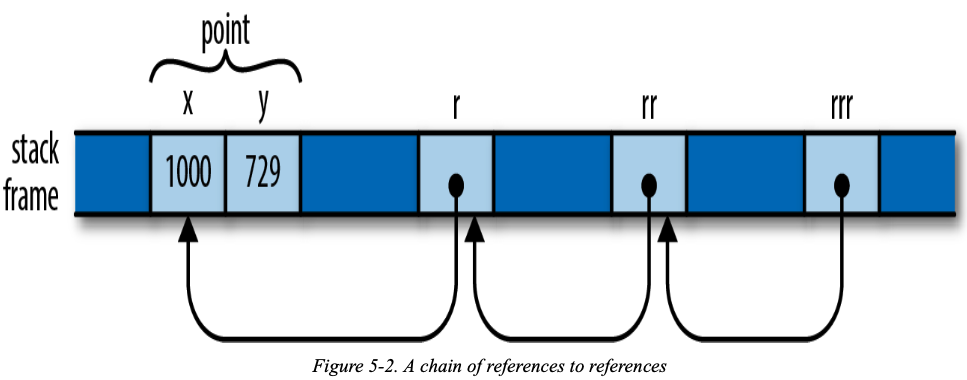

References to References

| |

The . operator follows as many references as it takes to find its target.

| |

So the expression rrr.y, guided by the type of rrr, actually traverses three references to get to the Point before fetching its y field.

Comparing References

| |

比较操作符和.操作符一样可以解引用到最终的目标值。

可以用std::ptr::eq来比较地址是否相等:

| |

比较操作符两端的类型必须相同:

| |

References Are Never Null

Rust references are never null. There is no default initial value for a reference (you can’t use any variable until it’s been initialized, regardless of its type) and Rust won’t convert integers to references (outside of unsafe code), so you can’t convert zero into a reference.

In Rust, if you need a value that is either a reference to something or not, use the type Option<&T>.

Borrowing References to Arbitrary Expressions

Rust lets you borrow a reference to the value of any sort of expression at all:

| |

Rust simply creates an anonymous variable to hold the expression’s value and makes the reference point to that. The lifetime of this anonymous variable depends on what you do with the reference:

- If you immediately assign the reference to a variable in a let statement (or make it part of some struct or array that is being immediately assigned), then Rust makes the anonymous variable live as long as the variable the let initializes.

- Otherwise, the anonymous variable lives to the end of the enclosing statement.

References to Slices and Trait Objects

fat pointers:

- A reference to a slice is a fat pointer, carrying the starting address of the slice and its length.

- Rust’s other kind of fat pointer is a trait object, a reference to a value that implements a certain trait. A trait object carries a value’s address and a pointer to the trait’s implementation appropriate to that value, for invoking the trait’s methods.

Reference Safety

Borrowing a Local Variable

You can’t borrow a reference to a local variable and take it out of the variable’s scope:

| |

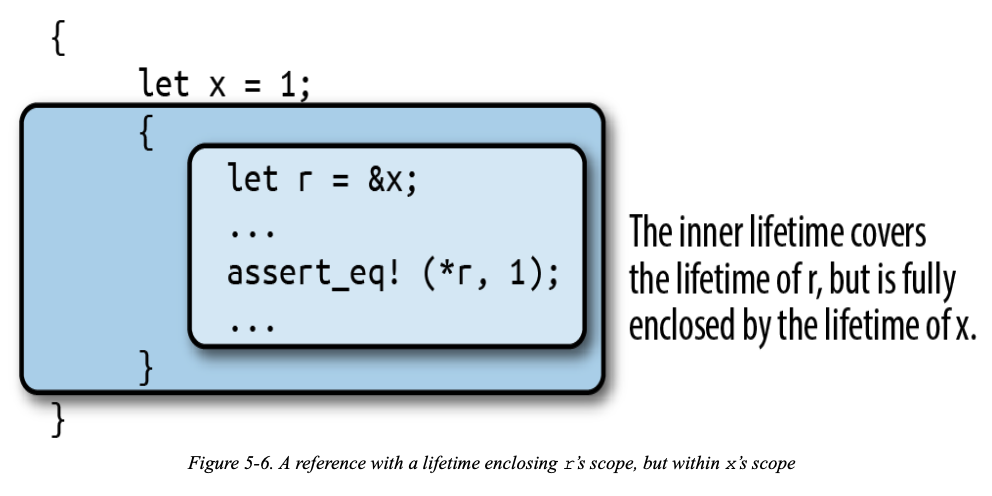

The variables r and x both have a lifetime, extending from the point at which they’re initialized until the point that the compiler can prove they are no longer in use. The third lifetime is that of a reference type: the type of the reference we borrow to x and store in r.

We say that the variable’s lifetime must contain or enclose that of the reference borrowed from it. 变量的生命周期必须包含或涵盖从它那里借来的引用的生命期。

Here’s another kind of constraint: if you store a reference in a variable r, the reference’s type must be good for the entire lifetime of the variable, from its initialization until its last us.

We say that the reference’s lifetime must contain or enclose the variable’s. 引用的生命期必须包含或涵盖保存它的变量的生命期。

The first kind of constraint limits how large a reference’s lifetime can be, while the second kind limits how small it can be.

下面的生命周期是正确的:

First, understand the constraints arising from the way the program uses references; then, find lifetimes that satisfy them.

Receiving References as Function Arguments

- Every static must be initialized.

- Mutable statics are inherently not thread-safe (after all, any thread can access a static at any time), and even in single-threaded programs, they can fall prey to other sorts of reentrancy problems. For these reasons, you may access a mutable static only within an unsafe block. In this example we’re not concerned with those particular problems, so we’ll just throw in an unsafe block and move on.

fn f<'a>(p: &'a i32), we’re defining a function that takes a reference to an i32 with any given lifetime ‘a.

In other words, we were unable to write a function that stashed a reference in a global variable without reflecting that intention in the function’s signature. In Rust, a function’s signature always exposes the body’s behavior.

If we do see a function with a signature like g(p: &i32) (or with the lifetimes written out, g<'a>(p: &'a i32)), we can tell that it does not stash its argument p anywhere that will outlive the call.

Passing References to Functions

| |

从g的签名看,Rust知道它不会把p保存到超出调用生命周期的变量里;任何涵盖调用的生命周期都满足'a。

| |

这里 &x不能存活得比x长,而函数签名要求&x活得和&'static一样长,这就无法得到满足,因此报错。

Returning References

| |

如果一个函数只有一个引用作为参数并返回一个引用,则它们拥有相同的生命周期。

Structs Containing References

当引用类型出现在另一个类型的定义中时,必须写出其生命周期。

| |

或者

| |

保存在r中的任何引用的生命周期最好包含'a,而'a也必须比保存在S的任何值都长寿。

The lifetime of any reference you store in r had better enclose ‘a, and ‘a must outlast the lifetime of wherever you store the S.

The assignment s = S { … } stores this S in a variable whose lifetime extends to the end of the example, constraining ‘a to outlast the lifetime of s.

And now Rust has arrived at the same contradictory constraints as before: ‘a must not outlive x, yet must live at least as long as s.

Distinct Lifetime Parameters

| |

如下代码:

| |

If you work through the code carefully, you can follow its reasoning:

- Both fields of S are references with the same lifetime ‘a, so Rust must find a single lifetime that works for both s.x and s.y.

- We assign r = s.x, requiring ‘a to enclose r’s lifetime. (r <= ‘a)

- We initialized s.y with &y, requiring ‘a to be no longer than y’s lifetime. (‘a <= y)

Omitting Lifetime Parameters

三条规则(见生命周期与引用有效性):

第一条规则是每一个是引用的参数都有它自己的生命周期参数。换句话说就是,有一个引用参数的函数有一个生命周期参数:

fn foo<'a>(x: &'a i32),有两个引用参数的函数有两个不同的生命周期参数,fn foo<'a, 'b>(x: &'a i32, y: &'b i32),依此类推。第二条规则是如果只有一个输入生命周期参数,那么它被赋予所有输出生命周期参数:

fn foo<'a>(x: &'a i32) -> &'a i32。第三条规则是如果方法有多个输入生命周期参数并且其中一个参数是

&self或&mut self,说明是个对象的方法(method)(译者注: 这里涉及 Rust 的面向对象参见 17 章), 那么所有输出生命周期参数被赋予self的生命周期。第三条规则使得方法更容易读写,因为只需更少的符号。

Sharing Versus Mutation

Throughout its lifetime, a shared reference makes its referent read-only: you may not assign to the referent or move its value elsewhere.

Shared access is read-only access.

Values borrowed by shared references are read-only. Across the lifetime of a shared reference, neither its referent, nor anything reachable from that referent, can be changed by anything. There exist no live mutable references to anything in that structure, its owner is held read-only, and so on. It’s really frozen.

Mutable access is exclusive access.

A value borrowed by a mutable reference is reachable exclusively via that reference. Across the lifetime of a mutable reference, there is no other usable path to its referent or to any value reachable from there. The only references whose lifetimes may overlap with a mutable reference are those you borrow from the mutable reference itself.

Taking Arms Against a Sea of Objects

Chapter 6. Expressions

Rust中绝大多数都是表达式。

An Expression Language

- 在Rust中,if 和 match 都可以产生值。一个match表达式可以给一个函数或者宏来传参。

- Rust 中没有三元操作符。

- Rust中所有的控制流程工具是表达式。

Precedence and Associativity

- 闭包的优先级在最后。

- All of the operators that can usually be chained are left-associative. 所有这些操作符在链式操作时都具有左关联性。

- 比较操作符,赋值操作符(assignment iperators)以及范围操作符(

..range operators)不能链式链接。

Blocks and Semicolons

- block 的值是最后一个表达式的值。

- let 声明必须要有分号。

- 如果 if 表达式没有 else,那么总是返回 ()。

Declarations

- let 声明必须要有分号。

- let 声明可以只声明变量而不初始化它。

- 在没有初始化一个变量之前是不能使用它的。

- 变量遮蔽,可以是不同的类型。

- 一个块可以包含特性项( item) declarations,就是指任何可以在程序或模块的全局中出现的声明,比如 fn,struct 或者 use。

- 嵌套的 fn 不能使用 scope 中的局部变量。

- 块中甚至可以包含一个完整的模块。

if and match

- if 表达式的 condition 必须是 bool 类型的,Rust 不会将数值或者指针隐式转换成 Boolean 类型。

- 在 if 表达式形式中,围绕条件的圆括号不是必需的。事实上,rustc在发现不必要的圆括号时会给出警告。但花括号是必需的。

- 一个只有 if 没有 else 的表达式相当于有一个 空的else 块。因此如果 if 表达式没有 else,那么总是返回

()。 - 编译器可以用一个跳转表( jump table )来优化 match 表达式。如果 match 的每个分支都产生一个常量值,那么也可以应用同样的优化。此时,编译器会构建一个这些值的数组,而 match 会被编译为对数组的访问。除了边界检查,编译后的代码中根本没有分支。

- Rust 禁止 match 表达式没有覆盖到所有情况。

- 一个 if 表达式的所有块必须产生相同类型的值,对于 match 表达式也是一样的,match 表达式的所有分支也都必须返回相同类型的值。

if let

| |

等价于

| |

Loops

有四种 looping 表达式:

| |

- while 和 for 的值一直都是 (),循环的值是

()。 - 用 loop 可以无限循环,除非遇到 break,return或者线程 panics。

for循环每迭代一个值就会消耗一个值,有时候可以使用引用。

Control Flow in Loops

- break 只能在 loop 中,不能在 match 中。

- 可以给 break 一个表达式,这个表达式的值就是 loop 的值。

- 自然地,所有 break 表达式在一个循环中必须是相同类型的,并且这个类型就是 loop 的类型。

- 循环可以加上生命周期的标签,然后可以 break 这个标签,break 也可以同时带上值表达式。

- 标签同样可以用于 continue。

return Expressions

- return 表达式会退出当前函数,并且给调用者返回一个值。

- 可以将函数体看成一个块表达式。

- return 可以放弃正在运行中的工作。

Why Rust Has loop

Rust编译器分析你的程序的控制流程:

- 检查返回类型

- 检查局部变量不会使用未初始化的值

- 警告不可到达的代码

以上这些称为流敏感(flow-sensitive)分析。

Rust追求简单,其流敏感分析压根不会检查循环条件,而只是假设程序中的任何条件不是true就是false。

! 表示是一个发散函数。比如 break,return,panic!(),无穷循环,std::process::exit() ,它们都不以惯常的方式结束,这些可以跳过之前说的类型一致规则。

Function and Method Calls

.location()方法可能取 player 的值或者引用。.操作符可以自动的解引用player或者借一个引用。可以接收值或引用。- 静态方法

Vec::new(),非静态方法通过值调用:my_vec.len()。 - 对于泛型,函数或者方法调用要用比目鱼 turbofish 操作符,比如:

return Vec::<i32>::with_capcity(1000);

Fields and Elements

点操作符或者方括号的左侧是一个引用或者智能指针,那么它可以被自动地解引用,这样的表达式被称为 lvalues,它们可以出现在一个 assignment 的左侧。

操作符:

| |

Reference Operators

- &

- & mut

*操作符可以用来解引用

Arithmetic, Bitwise, Comparsion, and Logical Operators

- 不能将

-和+用到无符号的数值类型上。 %也可以用在浮点数上。!表示按位非。- 位操作符的优先级高于比较操作符的优先级。

- 比较操作符两端的类型必须都是 bool 类型。

Assignment

- Rust中可以有复合操作符:

+=-=*= - Rust不支持链式 assignment,比如

a = b = 3 - Rust没有自增和自减操作符:

++和--。

Type Casts

可以用 as 进行类型转换。几种类型转换是允许的:

- 任何内置的数值之间可以转换。

- bool、char 或者 C-like enum 类型可以转换为整数。u8 可能转换为 char 类型。

- 有些含有 unsafe 的指针类型的转换也是允许的。

一些自动转换,被称为解引用强制转换(deref coercions):

&String->&str&Vec<i32>->&[i32]&Box[Chessboard]->&Chessboard

它们实现了内置的 Deref trait。

Closures

| |

Rust自动推断类型。调用闭包就像调用一个函数那样:

| |

Onward

表达式只是我们思考 running code。

Chapter 7. Error Handling

Panic

panic 是程序本身出现一个bug。比如:

- 数组越界

- 整数除零

- 对于一个

Result调用.expect()。 - 断言失败

panic时要么展开栈,要么中止程序,展开栈是默认的。

Unwinding

panic发生:

- 终端打印错误信息

- 运行

RUST_BACKTRACE=1会将栈展开。资源会关闭,会调用drop方法。 - 最后,线程退出。

panic不是崩溃,不是未定义行为。panic像Java中的运行时异常,其行为是明确定义的,只是不应该发生而已。

panic是安全的,它不违反任何Rust的安全规则。不会在内存中导致悬空指针或初始化一半的值,Rust展开栈后,进程的其他部分还可以运行。

panic是线程级别的。

有一种方法可以捕获栈展开,运行panic线程存活并继续运行。使用标准库中的std::panic::catch_unwind()函数。

Aborting

- 如果

.drop()方法触发了第二个panic当Rust在第一个panic后尝试 clean up,这会被当作是致命的。Rust会停止展开并且直接终止整个流程。 - 编译加上

-C panic=abort,第一个 panic 就立马终止程序。

Result

如果不使用Result值,会得到一个警告。

Catching Errors

用 match 来处理 error

| |

但是上面这种方式太冗长了。这里有一些方法:

| |

Result Type Aliases

在标准库 std::io 模块中有:

| |

这里用了 type aliases。

Printing Errors

std::io::Error、std::fmt::Error、std::str::Utf8Error等等实现了std::error::Error trait。一些公用的方法:

println!()打印错误,用

{}可以打印简短的错误信息,用{:?}的Debug模式打印出错误。err.to_string()返回错误信息字符串。

err.source()返回一个Option,包含潜在的错误。

| |

想要展开错误,在Rust不稳定版本下,可以使用anyhow包。

Propagating Errors

如果错误发生,我们希望调用者来处理。

| |

?操作符的行为取决于这个函数的返回值:

- 如果是成功结果,那么它会打开Result并取出其中的成功值。

- 如果是错误结果,那么它会立即从闭合函数中返回,将错误结果沿调用链向上传播。

?操作符一样可以使用match表达式实现。

?可以类似地用在Option类型的值上面。In a function that returns Option, you can use ? to unwrap a value and return early in the case of None.

Working with Multiple Error Types

?不能将std::num::ParseIntError转换为std::io::Error类型。- 所有标准库中的错误都可以转成

Box<dyn std::error::Error + Send + Sync + 'static'>类型。

| |

?会调用GenericError::from()方法来进行自动转换。

- 如果想要其中一种特别的错误类型进行处理,其它的错误进行传播的话,可以用泛型方法

error.downcast_ref::<ErrorType>()

Dealing with Errors That “Can’t Happen”

- 当我们不想处理不会发生的错误时,用

.unwrap()方法。 - 也可以用

.expect(message)方法。

Ingoring Errors

| |

用 let _ = ...用来禁止警告。

Handling Errors in main()

- 一般情况下在 main 函数中不能用

?,因为main()函数的返回类型不是Result。 - 最简单的方法是用

.expect()方法。发生错误时会 panic 并且返回一个非零的退出代码。 - 或者可以返回一个

Result类型,这样就能用?,同时用debug{:?}方式打印出错误。

| |

- 或者自己处理相应的错误。用

print_error()方法结合if let打印简介的错误信息。

Declaring a Custom Error Type

- 可以自定义

Error类型,用 struct 实现。Errors 应该实现fmt::Display和std::error::Errortrait。 - 或者直接用

thiserror中的,加上属性宏#[derive(Error)]。

| |

Why Results?

- 在代码中记录错误,对错误做出决定。

- 允许错误传播,传播路径可见。

- 每一个函数都有返回类型,这样更清楚函数可不可能失败。

- Rust 会检查 Result 类型的值是否被使用。

- 因为 Result 是一个数据类型,因此更容易处理一系列成功或者失败的值,也更容易存储。

Chapter 8. Crates and Modules

Crates

Rust programs are made of crates. Each crate is a complete, cohesive unit: all the source code for a single library or executable, plus any associated tests, examples, tools, configuration, and other junk.

要了解包是什么,以及它们如何协作,可以对一个使用了依赖的已有项目运行 cargo build 命令,同时加上 --verbose 标记。

Cargo 的依赖会形成 dependency graph 。

Cargo 会使用 --crate-type lib选项,会告诉 rustc 不要去找 main() 函数,而是生成一个 .rlib 文件,其中包含编译后的代码,可以供以后在创建库或者.rlib文件使用。

When compiling libraries, Cargo uses the – crate-type lib option. This tells rustc not to look for a main() function but instead to produce an .rlib file containing compiled code that can be used to create binaries and other .rlib files.

Cargo使用 --crate-type bin 选项,编译结果将是一个针对目标平台的二进制可执行文件。

运行每个 rustc 命令时,Cargo会通过--extern选项给出当前包用到的每个库的文件名。这样,当rustc看到use image::png::PNGEncoder这行代码时,它就知道到磁盘的什么位置去找这个库编码后的代码了。Rust编译器需要访问.rlib文件,因为其中包含第三方库编译后的代码。Rust会将这些代码静态链接到最终的可执行文件上。.rlib文件也包含类型信息,Rust可以据此检查我们代码中用到的库特性确实在对应的包里存在,从而保证正确地使用它们。这个文件里还包含包的公共内联函数、泛型和宏的一个副本,这些特性直到Rust遇到调用它们的代码时才会编译为机器码。

cargo build --release产生优化代码,优化代码的运行速度更快,但编译时间比较长,而且不会检查整型溢出,还会跳过debug_assert!()断言,另外它们针对 panic 生成的栈追踪信息一般不太可靠。

Editions

To evolve without breaking existing code, Rust uses editions. The 2015 edition of Rust is compatible with Rust 1.0. The 2018 edition changed async and await into keywords, streamlined the module system, and introduced various other language changes that are incompatible with the 2015 edition.

Rust promises that the compiler will always accept all extant editions of the language, and programs can freely mix crates written in different editions. It’s even fine for a 2015 edition crate to depend on a 2018 edition crate. In other words, a crate’s edition only affects how its source code is construed; edition distinctions are gone by the time the code has been compiled. This means there’s no pressure to update old crates just to continue to participate in the modern Rust ecosystem. Similarly, there’s no pressure to keep your crate on an older edition to avoid inconveniencing its users. You only need to change editions when you want to use new language features in your own code.

If you have a crate written in an older edition of Rust, the cargo fix command may be able to help you automatically upgrade your code to the newer edition. The Rust Edition Guide explains the cargo fix command in detail.

Build Profiles

构建分析

| 命令行 | Cargo.toml使用的区块 |

|---|---|

| cargo build | [profile.dev] |

| cargo build –realse | [profile.realse] |

| cargo test | [profile.test] |

想要同时启用优化和调试,可以这样设置:

| |

这里debug设置控制 rustc 中的 -g 选项。有了这个配置,再执行 cargo build --realse,就可以得到一个带有调试符号的二进制文件。优化设置不受影响。

Modules

| |

One function is marked pub(crate), meaning that it is available anywhere inside this crate, but isn’t exposed as part of the external interface. It can’t be used by other crates, and it won’t show up in this crate’s documentation.

Anything that isn’t marked pub is private and can only be used in the same module in which it is defined, or any child modules.

Nested Modules

mod可以嵌套。

It’s also possible to specifypub(super), making an item visible to the parent module only, and pub(in <path>), which makes it visible in a specific parent module and its descendants.

Modules in Separate Files

These three options—modules in their own file, modules in their own directory with a mod.rs, and modules in their own file with a supplementary directory containing submodules—give the module system enough flexibility to support almost any project structure you might desire.

Paths and Imports

用::操作符。

| |

或者用use导入。

| |

一次导入多个模块:

| |

导入时起别名

| |

模块不会自动从自己的父模块继承名字。关键字super是父模块的一个别名,self则是当前模块的一个别名,关键词 crate 表示包含当前模块的包。

| |

使用相对于根的路径,这样当模块移动时,也是有效的。

use super::*可以让子模块获得父模块的私有项。

绝对路径:

| |

The Standard Prelude

Furthermore, a few particularly handy names, like Vec and Result, are included in the standard prelude and automatically imported. Rust behaves as though every module, including the root module, started with the following import:

| |

The standard prelude contains a few dozen commonly used traits and types.

参考std::prelude。

Making use Declarations pub

| |

This means that Leaf and Root are public items of the plant_structures module. They are still simple aliases for plant_structures::leaves::Leaf and plant_structures::roots::Root.

Making Struct Fields pub

| |

Outside the module, only public fields are accessible.

Statics and Constants

| |

A constant is a bit like a C++ #define: the value is compiled into your code every place it’s used. A static is a variable that’s set up before your program starts running and lasts until it exits. Use constants for magic numbers and strings in your code. Use statics for larger amounts of data, or any time you need to borrow a reference to the constant value.

There are no mut constants.

Turning a Program into a Library

The first step is to factor your existing project into two parts: a library crate, which contains all the shared code, and an executable, which contains the code that’s only needed for your existing command-line program.

By default, cargo build looks at the files in our source directory and figures out what to build. When it sees the file src/lib.rs, it knows to build a library. The code in src/lib.rs forms the root module of the library. Other crates that use our library can only access the public items of this root module.

The src/bin Directory

We can keep our program and our library in the same crate, too. Put this code into a file named src/bin/efern.rs:

| |

Because we’ve put this file into src/bin, Cargo will compile both the fern_sim library and this program the next time we run cargo build. We can run the efern program using cargo run –bin efern. Here’s what it looks like, using –verbose to show the commands Cargo is running.

| |

可以将 fern_sim 作为一个单独的项目,然后在 Cargo.toml 上加上依赖。

Attributes

Rust程序中的任何 item 都可以用属性来修饰。

#[allow(non_camel_case_types)]可以不使用驼峰命名法。#[cfg]条件编译#[inline]内联函数。当出现一个函数或者一个方法定义在一个 crate 中,而我们在另一个 crate 中去调用,可以显式使用这个属性。#[inline(always)]要求函数在每一次调用的点都展开内联#[inline(never)]要求一个函数从不进行内联

#[cfg]和#[allow]可以用在一整个模块或者里面的任何东西,但是#[inline]和#[test]只能用在单个项上面。- 想在整个 crate 上面绑定属性,在main.rs

或者lib.rs文件顶部中用#!。#!也可以用在函数,结构体中,但是它只能一贯地用在文件的开头,来绑定给整个模块或者 crate 绑定一个属性。而有的属性总是用#!,因为它只能作用在整个 crate 上,比如#![feature]。 #![feature]用来表示 Rust 语言不稳定的 features,这些是实验性质的。当后面这个 feature 稳定之后,编译器就会警告,建议移除#![feature]。

Tests and Documention

#[test]标记函数,表明这个是测试函数,用cargo test可以测试所有测试函数,如果只想测试某一个,可以用cargo test name来测试具体的函数。assert!(expr):如果表达式为真就通过测试,否则 panic。assert_eq!(v1, v2):判别 v1 和 v2 是否相等。- 如果只想在 debug 模式下检验是否相等,可以用

debug_assert!和debug_assert_eq!。 #[should_panic]表示会 panic。或者返回Result<(), E>。cargo build和cargo build --realse会跳过#[test]测试代码。- 当运行

cargo test,cargo 会编译两次代码。一次是常规的,还有一次是测试程序并启用测试套件。 #[cfg(test)]标记整个模块。- 一般 cargo test 会启用多线程来一次运行多个测试,用

cargo test name和cargo test -- --test-threads 1来限制只用一个线程测试。 cargo test -- --no-capture:也输出那些通过的测试。

Integration Tests

- 集成测试,可以用来测试一些公共的API,站在用户的角度。

- 单独建立一个

tests的文件夹,放在和src同一个路径下,当运行cargo test的时候,集成测试和单元测试都会运行。如果只想运行集成测试,可以用命令cargo test --test unfurl来运行一个具体的集成测试。

Documentation

| |

- –no-deps :只生成自己的文档,不生成所有它依赖的 crates。

- –open:在浏览器中打开文档。

- 生成的文档放在 target/doc 目录下。

///的文档注释类似#[doc]属性。而//!和#![doc]一样。- 文档注释中markdown 的链接也可以链接到相应代码的文档。

- One special feature of doc comments in Rust is that Markdown links can use Rust item paths, like leaves::Leaf, instead of relative URLs, to indicate what they refer to.

| |

You can also add search aliases to make it easier to find things using the built-in search feature.

| |

文档中的代码:

| |

或者用Markdown格式:

| |

Doc-Tests

- Rust 也会测试在文档注释中的代码,会隐式的加在

fn main()函数里面。 - The idea behind doc-tests is not to put all your tests into comments. Rather, you write the best possible documentation, and Rust makes sure the code samples in your documentation actually compile and run.

- To hide a line of a code sample, put a # followed by a space at the beginning of that line.

- rustdoc therefore treats any code block containing the exact string fn main as a complete program and doesn’t add anything to it.

- To tell Rust to compile your example, but stop short of actually running it, use a fenced code block with the

no_runannotation. - If the code isn’t even expected to compile, use

ignoreinstead ofno_run. Blocks marked withignoredon’t show up in the output of cargo run, but no_run tests show up as having passed if they compile. - If the code block isn’t Rust code at all, use the name of the language, like c++ or sh, or text for plain text.

Specifying Dependencies

用版本号:

| |

Git仓库地址和修订版本号:

| |

可以指定使用哪个 rev、tag 或 branch。

另一种方式是指定包含依赖包源代码的目录:

| |

Versions

对于在 Cargo.toml 中写的 image = "0.6.1" ,Cargo 的解释并没有那么严格。它会使用与 0.6.1 版兼容的最新版本的 image 。

兼容性的判断基本上遵循“语义化版本”的思想。

- 以0.0开头的版本过于原始,Cargo不会假设它与任何其他版本兼容。

- 以0.x(基本x不是0)开头的版本,会被认为同其他以0.x开头的版本兼容。

- 如果项目达到1.0版,则只有新的主版本号才会破坏兼容性。

不同项目对依赖和版本有不同的需求。因此,指定版本时可以使用操作符。例如>、>=、<=。

使用通配符*表示任何版本都可以,这个并不多见。

Cargo.lock

在第一次构建项目时,Cargo会输出一个Cargo.lock文件,记录它使用的每个包的确切的版本号。如果手动修改了Cargo.toml文件中的版本号或者运行cargo update时,会把新版本号保存到Cargo.lock文件中。

对于保存在Git代码库的依赖也是类似的。

如果你的项目是一个可执行文件,应该把Cargo.lock提交到版本控制系统。如果是一个普通的Rust库,就不用提交Cargo.lock了。如果恰好你的项目是一个共享库,没有这种下游的cargo用户,那就应该提供Cargo.lock。

Publishing Crates to crates.io

cargo package 让Cargo打包。会创建一个.crate文件,其中包含库的源文件以及Cargo.toml。

cargo package --list可以查看其中包含什么文件。

| |

可以同时指定本地依赖和版本号,不过要保证二者同步:

| |

接着就是发布了:

| |

Workspace

使用Cargo工作空间可以节省编译时间和磁盘空间。所谓工作空间,就是共享相同构建目录和Cargo.lock文件的一组包。

要使用工作空间,只需在存储库的根目录下创建一个Cargo.toml文件,并把下面几行放进去:

| |

Here fern_sim etc. are the names of the subdirectories containing your crates. Delete any leftover Cargo.lock files and target directories that exist in those subdirectories.

The command cargo build --workspace builds all crates in the current workspace. cargo test and cargo doc accept the --workspace option as well.

Chapter 9. Structs

Rust has three kinds of struct types, named-field, tuple-like, and unit-like, which differ in how you refer to their components: a named-field struct gives a name to each component, whereas a tuple- like struct identifies them by the order in which they appear. Unit-like structs have no components at all; these are not common, but more useful than you might think.

Named-Field Structs

| |

结构体的名字用驼峰命名法,其中的字段用蛇形拼写法。

You can use key: value syntax for some fields and shorthand for others in the same struct expression.

To access a struct’s fields, use the familiar . operator.

可以将结构体设为pub,但是字段默认私有。这样可以通过一些公有的方法创建结构体或者修改它。

使用.. EXPR,任何没有出现的字段都将从EXPR中取得自己的值,前提是EXPR必须为同一结构体类型的另一个值。

Tuple-Like Structs

类元组结构体:

| |

通过.操作符来访问。

定义此结构体会隐式定义一个函数:

| |

newtypes,即只包含一个要经过更严格类型检查的组件的结构体。

| |

Unit-Like Structs

| |

这种类型的值不占任何内存,像()。

Rust doesn’t bother actually storing unit-like struct values in memory or generating code to operate on them, because it can tell everything it might need to know about the value from its type alone. But logically, an empty struct is a type with values like any other—or more precisely, a type of which there is only a single value.

Struct Layout

| |

一种可能的内存布局:

Rust不保证结构体的字段或元素在内存中会以某种顺序存储,但是保证把字段的值直接存储在结构体的内存块中。

Defining Methods with impl

Functions defined in an impl block are called associated functions, since they’re associated with a specific type. The opposite of an associated function is a free function, one that is not defined as an impl block’s item.

self&self&mut self

当调用方法时,. 操作符会隐式转换,如果方法定义的是借用,就会隐式转换为引用。注意self会移动所有权。

Passing Self as a Box, Rc, or Arc

A method’s self argument can also be a Box<Self>, Rc<Self>, or Arc<Self>. Such a method can only be called on a value of the given pointer type. Calling the method passes ownership of the pointer to it.

| |

Rust automatically borrows a reference from pointer types like Box, Rc, and Arc, so &self and &mut self are almost always the right thing in a method signature, along with the occasional self.

| |

If the caller has an Rc<Node> at hand, it can call append_to directly, passing the Rc by value:

| |

Again, for most methods, &self, &mut self, and self (by value) are all you need. But if a method’s purpose is to affect the ownership of the value, using other pointer types for self can be just the right thing.

Type-Associated Functions

| |

Separating a type’s methods from its definition may seem unusual, but there are several advantages to doing so:

- It’s always easy to find a type’s data members.

- Pulling methods out into an impl block allows a single syntax for all three. In fact, Rust uses this same syntax for defining methods on types that are not structs at all, such as enum types and primitive types like i32.

- The same impl syntax also serves neatly for implementing traits, which we’ll go into in Chapter 11.

Associated Consts

| |

使用:

| |

Generic Structs

| |

相关方法:

| |

使用Self:

| |

For associated function calls, you can supply the type parameter explicitly using the ::<> (turbofish) notation:

| |

Structs with Lifetime Parameters

| |

当然这里生命周期参数也可以省略,因为可以根据三条规则进行推断。

Deriving Common Traits for Struct Types

| |

Interior Mutability

支持内部可变性,用Cell<T>和RefCell<T>,定义在std::cell模块中。

Cell<T>是只包含一个T类型私有值的结构体。Cell唯一特别的地方是不需要对其自身的mut引用,你也能取得或设置其私有字段的值。

Cell::new(value):创建一个新Cell,将value转移到其中。cell.get():返回cell中值的副本。要求 cell 实现 Copy trait。cell.set(value):把value保存到cell,丢弃之间保存的值。

RefCell<T>是只包含一个T类型值的泛型类型。但与Cell不同,RefCell<T>支持借用它的T类型值的引用。

RefCell::new(value):创建一个新RefCell,将value转移到其中。ref_cell.borrow():返回一个Ref<T>,基本上是对 ref_cell 中值的共享引用。This method panics if the value is already mutably borrowed.ref_cell.borrow_mut(): Returns aRefMut<T>, essentially a mutable reference to the value in ref_cell. This method panics if the value is already borrowed.ref_cell.try_borrow(),ref_cell.try_borrow_mut(): Work just likeborrow()andborrow_mut(), but return aResult. Instead of panicking if the value is already mutably borrowed, they return anErrvalue.

This is a lot like how normal references work. The only difference is that normally, when you borrow a reference to a variable, Rust checks at compile time to ensure that you’re using the reference safely. If the checks fail, you get a compiler error. RefCell enforces the same rule using run-time checks. So if you’re breaking the rules, you get a panic (or an Err, for try_borrow and try_borrow_mut).

The other drawback is less obvious and more serious: cells—and any types that contain them—are not thread-safe.

补充:参考RefCell 和内部可变性模式。

- 因为

RefCell<T>允许在运行时执行可变借用检查,所以我们可以在即便RefCell<T>自身是不可变的情况下修改其内部的值。

结构体是“与”的逻辑,而枚举是“或”的逻辑。

Chapter 10. Enums and Patterns

Enums

| |

这个是标准库中的,导入用use。也可以自己定义枚举,自己导入。

| |

In memory, values of C-style enums are stored as integers. Occasionally it’s useful to tell Rust which integers to use:

| |

Otherwise Rust will assign the numbers for you, starting at 0.

By default, Rust stores C-style enums using the smallest built-in integer type that can accommodate them. Most fit in a single byte.

#[repr]可以自己选择枚举的内存表示。

可以将C式枚举转换为整数,但是反过来不可以。

和结构体一样,可以给枚举加上属性,定义相关方法。

Enums with Data

一个枚举可以同时包含三种变体:

| |

All constructors and fields of an enum share the same visibility as the enum itself.

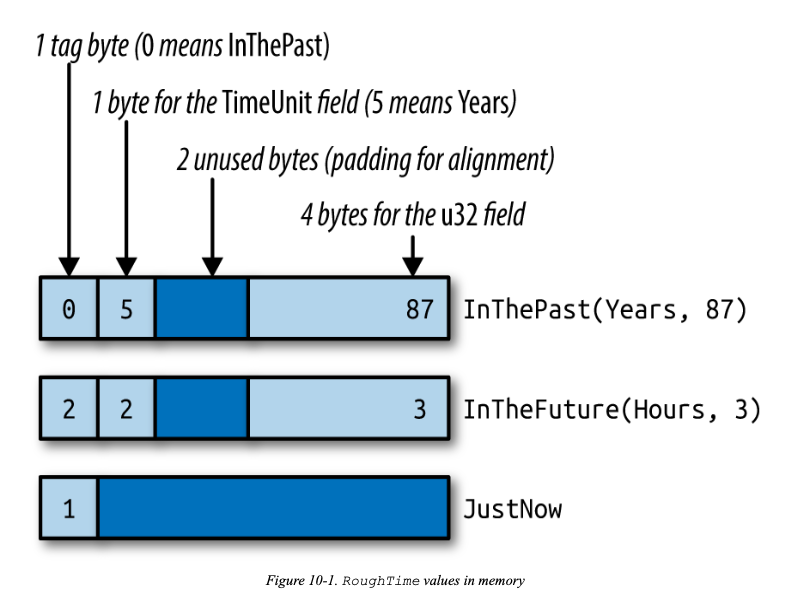

Enums in Memory

在内存中,带数据的每个构造式都需要一个小整数标签。

RoughTime的每个构造式占用8个字节。

为了方便优化,Rust并未对枚举的内存布局方式做出任何承诺。For instance, some generic structs can be stored without a tag at all, as we’ll see later.

Rich Data Structures Using Enums

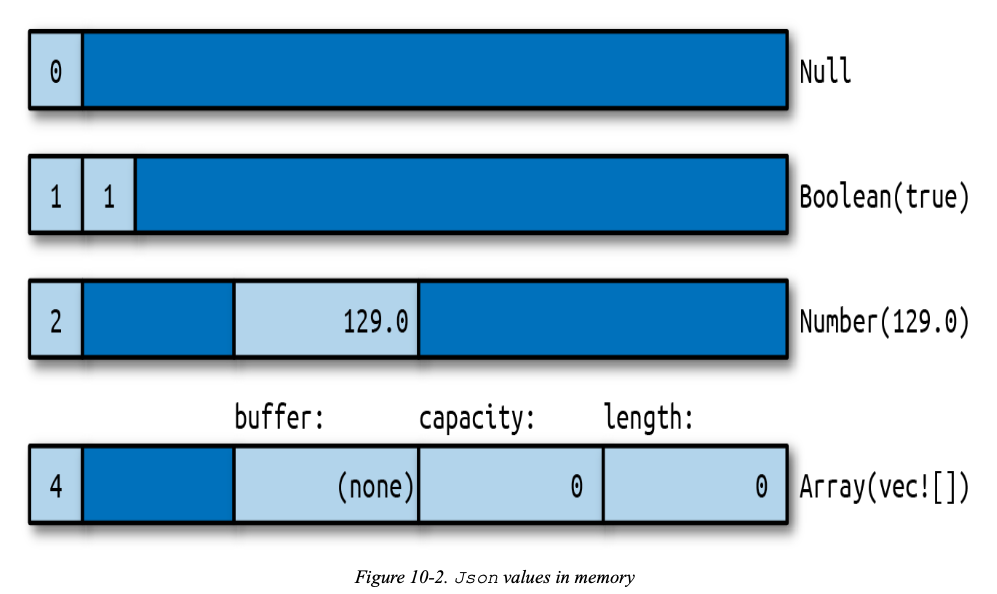

| |

内存布局:

在内存中,Json类型的值占4个机器字。String和Vec值占3个机器字,Rust还会加一个标签字节。Null和Boolean值用不了那么多内存空间,但所有Json值的大小必须相同。

Box<HashMap>只占一个机器字,因为它只是一个指向分配到堆内存数据的指针。

Generic Enums

| |

**如果类型T是引用或Box或其他智能指针类型,Rust就会省掉Option<T>的标签字段。**因此Option<Box<i32>>在内存中只用1个机器字节存储。0表示None,非零表示Some封装的值。

| |

访问枚举数据唯一的方式是一种安全的方式:使用模式。

Patterns

在枚举中不能直接通过.操作符访问枚举的字段。可以用match表达式来进行模式匹配。

表达式产生值,模式消费值。

模式匹配会从左到右对比模式的每个组件,依次检查当前值是否与之匹配。如果不匹配,就前进到下一个模式。

| 模式类型 | 示例 | 说明 |

|---|---|---|

| Literal | ||

| Range | ||

| Wildcard Variable | ||

| ref variable | ||

| Binding with subpattern | ||

| Enum pattern | ||

| Tuple pattern | ||

| Array pattern | ||

| Slice pattern | ||

| Struct pattern | ||

| Reference | ||

| Multiple patterns | `‘a’ | ‘A’` |

| Guard expression | x if x * x <= r2 | In match only (not valid in let, etc.) |

Literals, Variables, and Wildcards in Patterns

| |

可以使用通配符_。

| |

即便你非常确定其他情况不会发生,也必须至少加上一个后备的panic分支:

| |

Tuple and Struct Patterns

元组模式匹配元组:

| |

结构体模式使用花括号:

| |

在结构体模式匹配中,可以使用...来告诉Rust你并不关心其他字段:

| |

Array and Slice Patterns

数组匹配:

| |

切片匹配:

| |

Reference Patterns

对于引用,Rust支持两种模式:ref模式和&模式。前者借用匹配值的元素,后者匹配引用。

需要一种模式来借用而不move匹配的值。用关键字ref。

| |

使用ref mut借用mut引用:

| |

以&开头的模式匹配引用。

| |

表达式和模式天生是相反的。表达式(x, y)用两个值创建一个新元组,模式(x, y)则相反:它匹配元组并破坏后取出两个值。对&而言也一样:表达式&创建引用,模式中的&匹配引用。匹配引用中,生命周期是必要条件。不能对共享引用采取mut操作。不能从引用(包括mut引用)中move出值。

| |

修改:

| |

可以使用&模式取得引用所指向的字符:

| |

Match Guards

| |

But Rust also provides match guards, extra conditions that must be true in order for a match arm to apply, written as if CONDITION, between the pattern and the arm’s => token:

| |

If the pattern matches, but the condition is false, matching continues with the next arm.

Matching Multiple Possibilities

| |

或者

| |

Binding with @ Patterns

x @ pattern匹配给定的 pattern,但成功之后,不是基于匹配值的元素来创建变量,而是把匹配值整个移动或复制到一个变量 x 中。

| |

@ patterns are also useful with ranges:

| |

Where Patterns Are Allowed

The meaning is always the same: instead of just storing a value in a single variable, Rust uses pattern matching to take the value apart.

| |

上面的都是 irrefutable patterns,下面的是refutable pattern。

| |

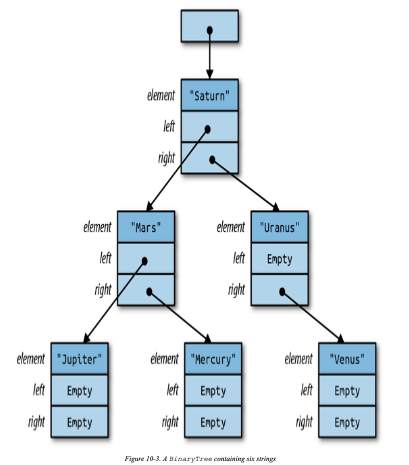

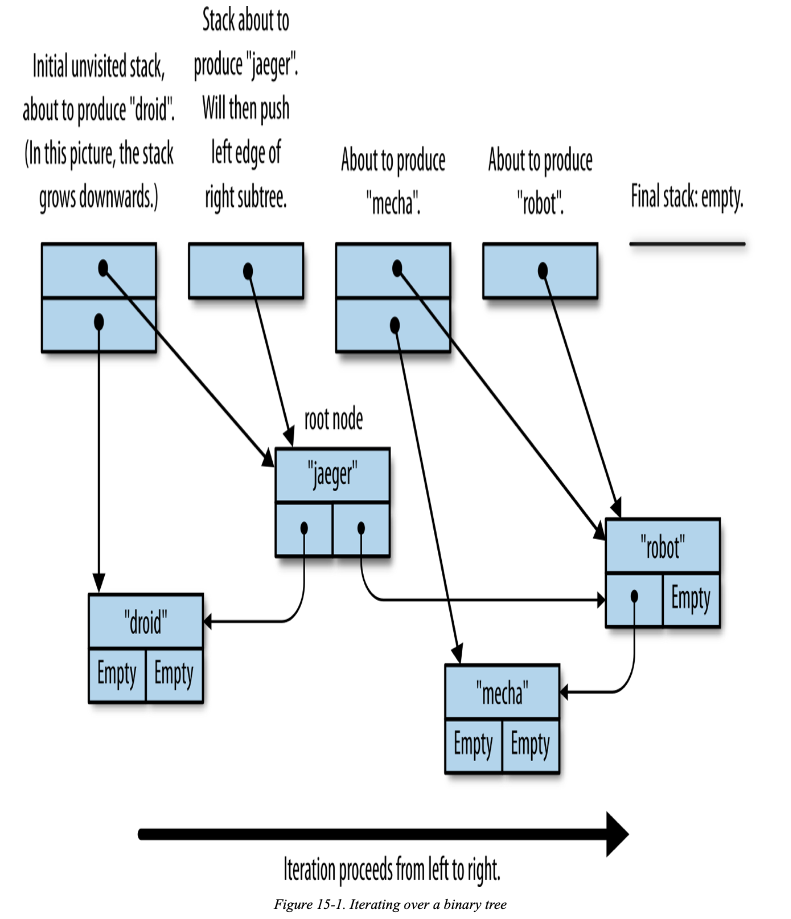

Populating a Binary Tree

| |

Chapter 11. Traits and Generics

Rust supports polymorphism with two related features: traits and generics.

Generics and traits are closely related: generic functions use traits in bounds to spell out what types of arguments they can be applied to. So we’ll also talk about how &mut dyn Write and <T: Write> are similar, how they’re different, and how to choose between these two ways of using traits.

Using Traits

- A value that implements

std::io::Writecan write out bytes. - A value that implements

std::iter::Iteratorcan produce a sequence of values. - A value that implements

std::clone::Clonecan make clones of itself in memory. - A value that implements

std::fmt::Debugcan be printed using println!() with the {:?} format specifier.

trait本身必须在作用域中。否则,trait的所有方法都是隐藏的。

But since Rust makes you import the traits you plan to use, crates are free to take advantage of this superpower. To get a conflict, you’d have to import two traits that add a method with the same name to the same type. This is rare in practice. (If you do run into a conflict, you can spell out what you want using fully qualified method syntax, covered later in the chapter.)

The reason Clone and Iterator methods work without any special imports is that they’re always in scope by default: they’re part of the standard prelude, names that Rust automatically imports into every module.

Trait Objects

Rust doesn’t permit variables of type dyn Write:

| |

A variable’s size has to be known at compile time, and types that implement Write can be any size.

| |

A reference to a trait type, like writer, is called a trait object. Like any other reference, a trait object points to some value, it has a lifetime, and it can be either mut or shared.

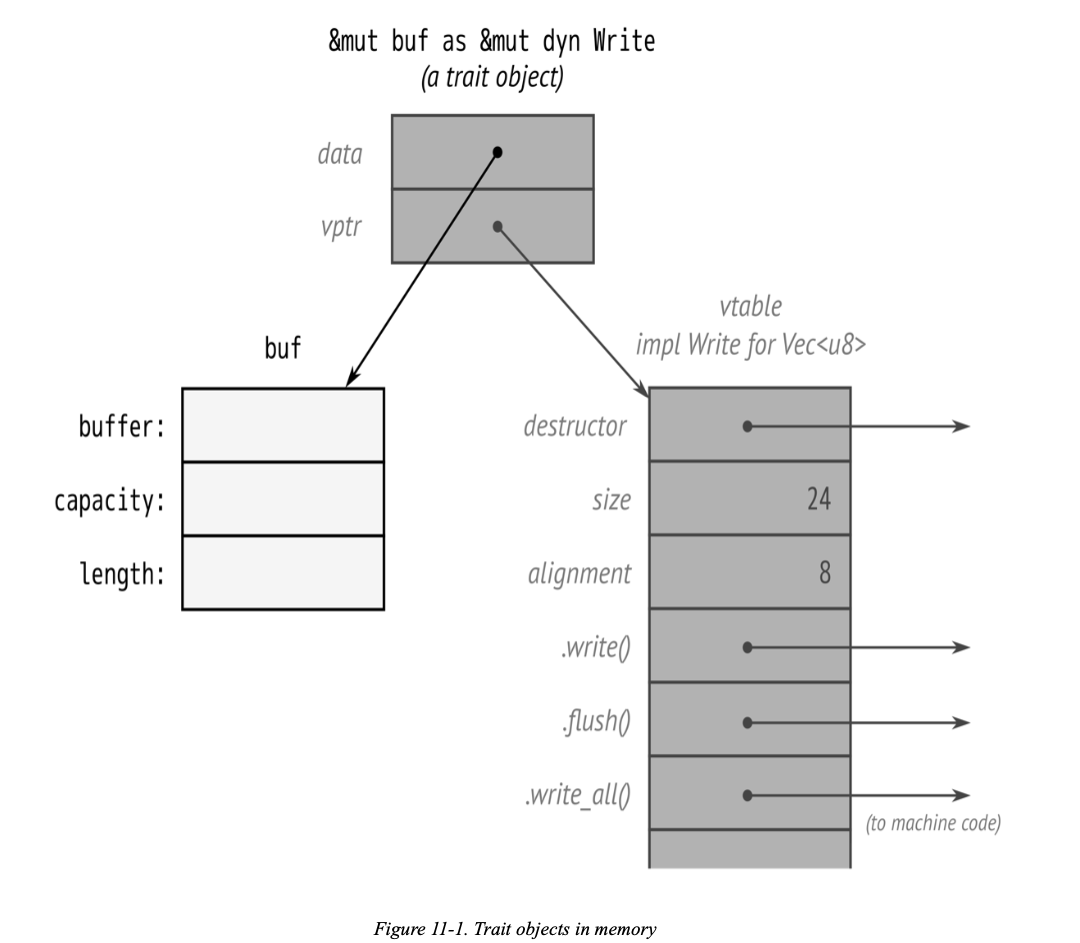

Trait object layout

In memory, a trait object is a fat pointer consisting of a pointer to the value, plus a pointer to a table representing that value’s type. Each trait object therefore takes up two machine words.

In Rust, as in C++, the vtable is generated once, at compile time, and shared by all objects of the same type. Everything shown in the darker shade in Figure 11-1, including the vtable, is a private implementation detail of Rust. Again, these aren’t fields and data structures that you can access directly. Instead, the language automatically uses the vtable when you call a method of a trait object, to determine which implementation to call.

Rust automatically converts ordinary references into trait objects when needed.

| |

Likewise, Rust will happily convert a Box<File> to a Box<dyn Write>, a value that owns a writer in the heap:

| |

This kind of conversion is the only way to create a trait object. What the compiler is actually doing here is very simple. At the point where the conversion happens, Rust knows the referent’s true type (in this case, File), so it just adds the address of the appropriate vtable, turning the regular pointer into a fat pointer.

Generic Functions and Type Parameters

| |

| |

This process is known as monomorphization, and the compiler handles it all automatically.

| |

| |

生命周期参数:

| |

生命周期不会对机器码有任何影响。

All the features introduced in this section—bounds, where clauses, lifetime parameters, and so forth—can be used on all generic items, not just functions.

Which to Use

| |

沙拉结构体用泛型函数实现,但是只能放一种蔬菜。

考虑到蔬菜值的大小可能差别比较大,不能直接用 Vec。

| |

可以这样实现:

| |

Another possible reason to use trait objects is to reduce the total amount of compiled code.

那么在不考虑沙拉或者low-resource environments这两种情况下,选择泛型函数有三个优点:

- The first advantage is speed. 会通过静态分发的方式,消除动态查找的时间。

- The second advantage of generics is that not every trait can support trait objects.

- The third advantage of generics is that it’s easy to bound a generic type parameter with several traits at once, as our top_ten function did when it required its T parameter to implement Debug + Hash + Eq. Trait objects can’t do this: types like &mut (dyn Debug + Hash + Eq) aren’t supported in Rust. (You can work around this with subtraits, defined later in this chapter, but it’s a bit involved.)

Defining and Implementing Traits

定义trait:

| |

实现trait,用impl TraitName for Type。

Everything defined in a trait impl must actually be a feature of the trait.

不在trait里的辅助方法要单独放在impl Type里面实现。而且实现trait时也可以调用这个辅助方法。

Default Methods

trait的默认实现:

| |

Traits and Other People’s Types

Rust lets you implement any trait on any type, as long as either the trait or the type is introduced in the current crate.

The sole purpose of this particular trait is to add a method to an existing type, char. This is called an extension trait.

| |

You can even use a generic impl block to add an extension trait to a whole family of types at once.

| |

We said earlier that when you implement a trait, either the trait or the type must be new in the current crate. This is called the orphan rule. It helps Rust ensure that trait implementations are unique.

Self in Traits

| |

Self作为返回类型意味着x.clone()的类型就是x的类型,不管具体什么类型。

使用Self类型的trait与trait objects不能共存。

| |

Rust rejects this code because it has no way to type-check the call left.splice(right). The whole point of trait objects is that the type isn’t known until run time. Rust has no way to know at compile time if left and right will be the same type, as required.

| |

There’s no problem type-checking calls to this .splice() method because the type of the argument other is not required to match the type of self, as long as both types are MegaSpliceable.

Subtraits

| |

Here, we say that Creature is a subtrait of Visible, and that Creature is Visible’s supertrait.

But in Rust, a subtrait does not inherit the associated items of its supertrait; each trait still needs to be in scope if you want to call its methods.

In fact, Rust’s subtraits are really just a shorthand for a bound on Self. A definition of Creature like this is exactly equivalent to the one shown earlier:

| |

Type-Associated Functions

Traits can include type-associated functions, Rust’s analog to static methods:

| |

If you want to use &dyn StringSet trait objects, you must change the trait, adding the bound where Self: Sized to each associated function that doesn’t take a self argument by reference:

| |

With these additions, StringSet trait objects are allowed; they still don’t support new or from_slice, but you can create them and use them to call .contains() and .add().

Fully Qualified Method Calls

| |

With fully qualified calls, you can say exactly which method you mean, and that can help in a few odd cases:

- When two methods have the same name.

1 2 3 4outlaw.draw(); // error: draw on screen or draw pistol? Visible::draw(&outlaw); // ok: draw on screen HasPistol::draw(&outlaw); // ok: corral - When the type of the self argument can’t be inferred:

1 2 3 4 5 6let zero = 0; // type unspecified; could be `i8`, `u8`, ... zero.abs(); // error: can't call method `abs` // on ambiguous numeric type i64::abs(zero); // ok - When using the function itself as a function value:

1 2 3 4let words: Vec<String> = line.split_whitespace() // iterator produces &str values .map(ToString::to_string) // ok .collect(); - When calling trait methods in macros.

Traits That Define Relationships Between Types

Traits can also be used in situations where there are multiple types that have to work together. They can describe relationships between types.

Associated Types (or How Iterators Work)

| |

The first feature of this trait, type Item;, is an associated type.

| |

trait object:

| |

Generic Traits (or How Operator Overloading Works)

| |

The type parameter here means the same thing that it means on a struct or function: Mul is a generic trait, and its instances Mul<f64>, Mul<String>, Mul<Size>, etc., are all different traits.

Generic traits get a special dispensation when it comes to the orphan rule: you can implement a foreign trait for a foreign type, so long as one of the trait’s type parameters is a type defined in the current crate.

| |

The syntax RHS=Self means that RHS defaults to Self. If I write impl Mul for Complex, without specifying Mul’s type parameter, it means impl Mul<Complex> for Complex. In a bound, if I write where T: Mul, it means where T: Mul<T>.

impl Trait

| |

这种写法太繁琐,可以这样写:

| |

但是这是动态分发,影响效率。可以使用 impl Trait。

| |

| |

It’s important to note that Rust doesn’t allow trait methods to use impl Trait return values.

| |

There is one important exception. Using generics allows callers of the function to specify the type of the generic arguments, like print::<i32>(42), while using impl Trait does not.

Associated Consts

| |

| |

Reverse-Engineering Bounds

和编译器做斗争,加上 Bounds。

| |

或者用第三方库num。

| |

Rust为什么要这样设计呢?为什么不模仿“鸭子类型”?这样设计的优点是:

- 可以让泛型代码具有向前兼容的能力。

- 你能通过编译器保存就知道要解决的麻烦在哪里。

- 或许,明确写出绑定最重要的好处是它们在代码和文档里都存在。

Traits as a Foundation

Traits are one of the main organizing features in Rust, and with good reason. There’s nothing better to design a program or library around than a good interface.

Chapter 12. Operator Overloading

The traits for operator overloading fall into a few categories depending on what part of the language they support.

| 类别 | Trait | 操作符 |

|---|---|---|

| Unary operators | std::ops::Neg | -x |

| std::ops::Not | !x | |

| Arithmetic operators | std::ops::Add | x + y |

| std::ops::Sub | x - y | |

| std::ops::Mul | x * y | |

| std::ops::Div | x / y | |

| std::ops::Rem | x % y | |

| Bitwise operators | std::ops::BitAnd | x & y |

| std::ops::BitOr | `x | |

| std::ops::BitXor | x ^ y | |

| std::ops::Shl | x << y | |

| std::ops::Shr | x >> y | |

| Compound assignment | std::ops::AddAssign | x += y |

| arithmetic operators | std::ops::SubAssign | x -= y |

| std::ops::MulAssign | x *= y | |

| std::ops::DivAssign | x /= y | |

| std::ops::RemAssign | x %= y | |

| Compound assignment | std::ops::BitAddAssign | x &= y |

| bitwise operators | std::ops::BitOrAssign | `x |

| std::ops::BitXorAssign | x ^= y | |

| std::ops::ShlAssign | x <<= y | |

| std::ops::ShrAssign | x >>= y | |

| Comparison | std::cmp::PartialEq | x == y, x != y |

| std::cmp::PartialOrd | x < y, x <= y, x > y, x >= y | |

| Indexing | std::ops::Index | x[y]、&x[y] |

| std::ops::IndexMut | x[y] = z、&mut x[y] |

Arithmetic and Bitwise Operators

std::ops::Add定义:

| |

实现:

| |

混合实现,加法的左边和右边不要求是同一类型:

| |

Unary Operators

Note that ! complements bool values and performs a bitwise complement (that is, flips the bits) when applied to integers; it plays the role of both the ! and ~ operators from C and C++.

| |

复数的实现:

| |

Binary Operators

All of Rust’s numeric types implement the arithmetic operators. Rust’s integer types and bool implement the bitwise operators. There are also implementations that accept references to those types as either or both operands.

You can use the + operator to concatenate a String with a &str slice or another String. However, Rust does not permit the left operand of + to be a &str, to discourage building up long strings by repeatedly concatenating small pieces on the left. (This performs poorly, requiring time quadratic in the final length of the string.)

Compound Assignment Operators

A compound assignment expression is one like x += y or x &= y: it takes two operands, performs some operation on them like addition or a bitwise AND, and stores the result back in the left operand. In Rust, the value of a compound assignment expression is always (), never the value stored.

Many languages have operators like these and usually define them as shorthand for expressions like x = x + y or x = x & y. However, Rust doesn’t take that approach. Instead, x += y is shorthand for the method call x.add_assign(y), where add_assign is the sole method of the std::ops::AddAssign trait:

| |

The built-in trait for a compound assignment operator is completely independent of the built-in trait for the corresponding binary operator.

Equivalence Comparisons

| |

用属性快速实现:

| |

Rust’s automatically generated implementation is essentially identical to our hand-written code, comparing each field or element of the type in turn.

This means that comparing non-Copy values like Strings, Vecs, or HashMaps doesn’t cause them to be moved, which would be troublesome:

| |

Why is this trait called PartialEq? The traditional mathematical definition of an equivalence relation, of which equality is one instance, imposes three requirements. For any values x and y:

对称性:If x == y is true, then y == x must be true as well. In other words, swapping the two sides of an equality comparison doesn’t affect the result.

传递性:If x == y and y == z, then it must be the case thatx == z. Given any chain of values, each equal to the next, each value in the chain is directly equal to every other. Equality is contagious.

自反性:It must always be true that x == x.

PartialEq只实现了前两条,自反性不保证,比如f32和f64就不满足。0.0/0.0会产生非数字的值NaN。

| |

Eq Trait:

| |

也可以用属性来快速实现:

| |

Ordered Comparisons

std::cmp::PartialOrd:

| |

| |

But if partial_cmp returns None, that means self and other are unordered with respect to each other: neither is greater than the other, nor are they equal. Among all of Rust’s primitive types, only comparisons between floating-point values ever return None: specifically, comparing a NaN (not-a-number) value with anything else returns None.

If you know that values of two types are always ordered with respect to each other, then you can implement the stricter std::cmp::Ord trait:

| |

Almost all types that implement PartialOrd should also implement Ord. In the standard library, f32 and f64 are the only exceptions to this rule.

排序应该同时实现 Partial Ord 和 Ord 。You might want to sort by upper bound, for instance, and it’s easy to do that with sort_by_key:

| |

The Reverse wrapper type takes advantage of this by implementing Ord with a method that simply inverts any ordering.

| |

Index and IndexMut

On any other type, the expression a[i] is normally shorthand for *a.index(i), where index is a method of the std::ops::Index trait. However, if the expression is being assigned to or borrowed mutably, it’s instead shorthand for *a.index_mut(i), a call to the method of the std::ops::IndexMut trait.

| |

You can refer to a subslice with an expression like a[i..j] because they also implement Index<Range<usize>>. That expression is shorthand for:

| |

| |

The Index trait’s associated type Output specifies what type an indexing expression produces: for our HashMap, the Index implementation’s Output type is i32.

Rust automatically selects index_mut when the indexing expression occurs in a context where it’s necessary.

| |

后两行和下面的代码一样:

| |

One limitation of IndexMut is that, by design, it must return a mutable reference to some value.

The most common use of indexing is for collections.

This is how Index and IndexMut implementations are supposed to behave: out-of-bounds access is detected and causes a panic, the same as when you index an array, slice, or vector out of bounds.

Other Operators

Not all operators can be overloaded in Rust. As of Rust 1.50, the error-checking ? operator works only with Result and Option values, though work is in progress to expand this to user-defined types as well. Similarly, the logical operators && and || are limited to Boolean values only. The .. and ..= operators always create a struct representing the range’s bounds, the & operator always borrows references, and the = operator always moves or copies values. None of them can be overloaded.

Rust does not support overloading the function call operator, f(x). Instead, when you need a callable value, you’ll typically just write a closure.

Chapter 13. Utility Traits

Language extension traits

- Drop, Deref and DerefMut

- From and Into

Marker traits

- Sized

- Copy

Public vocabulary traits

- Default

- AsRef, AsMut, Borrow and BorrowMut

- TryFrom and TryInto

- ToOwned

| Trait | Description |

|---|---|

| Drop | Destructors. Cleanup code that Rust runs automatically whenever a value is dropped. |

| Sized | Marker trait for types with a fixed size known at compile time, as opposed to types (such as slices) that are dynamically sized. |

| Clone | Types that support cloning values. |

| Copy | Marker trait for types that can be cloned simply by making a byte-for-byte copy of the memory containing the value. |

| Deref and DerefMut | Traits for smart pointer types. |

| Default | Types that have a sensible “default value.” |

| AsRef and AsMut | Conversion traits for borrowing one type of reference from another. |

| Borrow and BorrowMut | Conversion traits, like AsRef/AsMut, but additionally guaranteeing consistent hashing, ordering, and equality. |

| From and Into | Conversion traits for transforming one type of value into another. |

| TryFrom and TryInto | Conversion traits for transforming one type of value into another, for transformations that might fail. |

| ToOwned | Conversion trait for converting a reference to an owned value. |

Drop

std::ops::Drop trait

| |

This implicit invocation of drop is the only way to call that method; if you try to invoke it explicitly yourself, Rust flags that as an error.

If a variable’s value gets moved elsewhere, so that the variable is uninitialized when it goes out of scope, then Rust will not try to drop that variable: there is no value in it to drop. Although a value may be moved from place to place, Rust drops it only once.

You usually won’t need to implement std::ops::Drop unless you’re defining a type that owns resources Rust doesn’t already know about.

If a type implements Drop, it cannot implement the Copy trait. If a type is Copy, that means that simple byte-for-byte duplication is sufficient to produce an independent copy of the value. But it is typically a mistake to call the same drop method more than once on the same data.

The standard prelude includes a function to drop a value, drop, but its definition is anything but magical:

| |

从调用者那里获得所有权,然后什么也不做。Rust会在超出作用域时清楚_x的值,跟清除其他变量的值一样。

Sized

A sized type is one whose values all have the same size in memory.

All sized types implement the std::marker::Sized trait, which has no methods or associated types. Rust implements it automatically for all types to which it applies; you can’t implement it yourself. The only use for Sized is as a bound for type variables: a bound like T: Sized requires T to be a type whose size is known at compile time. Traits of this sort are called marker traits, because the Rust language itself uses them to mark certain types as having characteristics of interest.

Rust can’t store unsized values in variables or pass them as arguments. You can only deal with them through pointers like &str or Box<dyn Write>, which themselves are sized.

In fact, this is necessary so often that it is the implicit default in Rust: if you write struct S<T> { ... }, Rust understands you to mean struct S<T: Sized> { ... }. If you do not want to constrain T this way, you must explicitly opt out, writing struct S<T: ?Sized> { ... }. The ?Sized syntax is specific to this case and means “not necessarily Sized.” For example, if you write struct S<T: ?Sized> { b: Box<T> }, then Rust will allow you to write S<str> and S<dyn Write>, where the box becomes a fat pointer, as well as S<i32> and S<String>, where the box is an ordinary pointer.

Aside from slices and trait objects, there is one more kind of unsized type. A struct type’s last field (but only its last) may be unsized, and such a struct is itself unsized.

| |

Clone

std::clone::Clone

| |

clone_from方法将self修改为source的一个副本。这个方法的默认定义知识简单地克隆了source,然后将副本转移到*self中。语句s = t.clone();必须先克隆t,清除s原来的值,然后再将克隆的值转移到s中。这涉及一次堆分配和一次堆释放。在泛型代码中,应该尽可能使用clone_from,从而在可能的情况下应用这种优化。

加上#[derive(Clone)]实现。

没有实现Clone:std::sync::Mutex、stf::file::File(但是提供了一个try_clone()方法)。

Copy

A type is Copy if it implements the std::marker::Copy marker trait, which is defined as follows:

| |

But because Copy is a marker trait with special meaning to the language, Rust permits a type to implement Copy only if a shallow byte-for-byte copy is all it needs. Types that own any other resources, like heap buffers or operating system handles, cannot implement Copy. Any type that implements the Drop trait cannot be Copy. Rust presumes that if a type needs special cleanup code, it must also require special copying code and thus can’t be Copy.

As with Clone, you can ask Rust to derive Copy for you, using #[derive(Copy)]. You will often see both derived at once, with #[derive(Copy, Clone)].

Deref and DerefMut

std::ops::Deref

| |

std::ops::DerefMut

| |

Since the methods return a reference with the same lifetime as &self, self remains borrowed for as long as the returned reference lives.

由于deref接收&self引用并返回&Self::Target引用,因此Rust会利用这一点自动将前一种类型的引用转换为后一种类型的引用。换一句话说,如果插入一次deref调用可以防止类型错配,那Rust会为你插入一次。实现DerefMut可以实现对可修改引用的类型转换。这种类型转换称为解引用强制转型(deref coercion),即一种类型被“强制”表现出另一种类型的行为。

使用解引用强制类型转换很方便:

Rc<T>实现了Deref<Target=T>String实现了Deref<Target=str>Vec<T>实现了Deref<Target=[T]>

必要情况下,Rust会连续多次应用解引用强制转换。

Deref和DerefMut trait的设计初衷是为了实现智能指针类型(如Box、Rc和Arc),以及某些频繁通过引用来使用的类型的所有者版本(如Vec<T>和String就是[T]和str的所有者版本)。

Rust通过应用解引用强制转换来解决类型冲突,但不会应用它来满足类型变量的绑定。

| |

Rust不会在满足类型变量的绑定时应用解引用强制类型转换,所以检查失败。

| |

Default

std::default::Default

| |

| |

But of course, partition isn’t specific to HashSets; you can use it to produce any sort of collection you like, as long as the collection type implements Default, to produce an empty collection to start with, and Extend<T>, to add a T to the collection. String implements Default and Extend<char>, so you can write:

| |

Another common use of Default is to produce default values for structs that represent a large collection of parameters, most of which you won’t usually need to change.

| |

If a type T implements Default, then the standard library implements Default automatically for Rc<T>, Arc<T>, Box<T>, Cell<T>, RefCell<T>, Cow<T>, Mutex<T>, and RwLock<T>. The default value for the type Rc<T>, for example, is an Rc pointing to the default value for type T.

如果元组类型的所有类型都实现了Default,且该该元组类型也实现了Default,那么这个元组默认会持有每个元素的默认值。

Rust does not implicitly implement Default for struct types, but if all of a struct’s fields implement Default, you can implement Default for the struct automatically using # [derive(Default)].

AsRef and AsMut

std::convert::AsRef

| |

std::convert::RefMut

| |

So, for example, Vec<T> implements AsRef<[T]>, and String implements AsRef<str>. You can also borrow a String’s contents as an array of bytes, so String implements AsRef<[u8]> as well.

But this can’t be the whole story. A string literal is a &str, but the type that implements AsRef<Path> is str, without an &. And as we explained in “Deref and DerefMut”, Rust doesn’t try deref coercions to satisfy type variable bounds, so they won’t help here either.

Fortunately, the standard library includes the blanket implementation:

| |

In other words, for any types T and U, if T: AsRef<U>, then &T: AsRef<U> as well: simply follow the reference and proceed as before.

You might assume that if a type implements AsRef

Borrow and BorrowMut

The std::borrow::Borrow trait is similar to AsRef: if a type implements Borrow<T>, then its borrow method efficiently borrows a &T from it. But Borrow imposes more restrictions: a type should implement Borrow

| |

Borrow is designed to address a specific situation with generic hash tables and other associative collection types.

| |

Vec

The standard library includes a blanket implementation so that every type T can be borrowed from itself: T: Borrow

std::borrow::BorrowMut

| |

From and Into

The std::convert::From and std::convert::Into traits represent conversions that consume a value of one type and return a value of another.

| |

The standard library automatically implements the trivial conversion from each type to itself: every type T implements From<T> and Into<T>.

You generally use Into to make your functions more flexible in the arguments they accept.

The from method serves as a generic constructor for producing an instance of a type from some other single value.

Given an appropriate From implementation, the standard library automatically implements the corresponding Into trait.

However, cheap conversions are not part of Into and From’s contract. Whereas AsRef and AsMut conversions are expected to be cheap, From and Into conversions may allocate, copy, or otherwise process the value’s contents.

The ? operator uses From and Into to help clean up code in functions that could fail in multiple ways by automatically converting from specific error types to general ones when needed.

| |

| |

From and Into are infallible traits—their API requires that conversions will not fail.

TryFrom and TryInto

Instead, i32 implements TryFrom

| |

Where From and Into relate types with simple conversions, TryFrom and TryInto extend the simplicity of From and Into conversions with the expressive error handling afforded by Result. These four traits can be used together to relate many types in a single crate.

ToOwned

The std::borrow::ToOwned trait provides a slightly looser way to convert a reference to an owned value:

| |

Borrow and ToOwned at Work: The Humble Cow

But in some cases you cannot decide whether to borrow or own until the program is running ; the std::borrow::Cow type (for “clone on write”) provides one way to do this.

| |

A Cow<B> either borrows a shared reference to a B or owns a value from which we could borrow such a reference. Since Cow implements Deref, you can call methods on it as if it were a shared reference to a B: if it’s Owned, it borrows a shared reference to the owned value; and if it’s Borrowed, it just hands out the reference it’s holding.

You can also get a mutable reference to a Cow’s value by calling its to_mut method, which returns a &mut B. If the Cow happens to be Cow::Borrowed, to_mut simply calls the reference’s to_owned method to get its own copy of the referent, changes the Cow into a Cow::Owned, and borrows a mutable reference to the newly owned value. This is the “clone on write” behavior the type’s name refers to.

One common use for Cow is to return either a statically allocated string constant or a computed string.

| |

Chapter 14. Closures

It’s more concise to write the helper function as a closure, an anonymous function expression:

| |

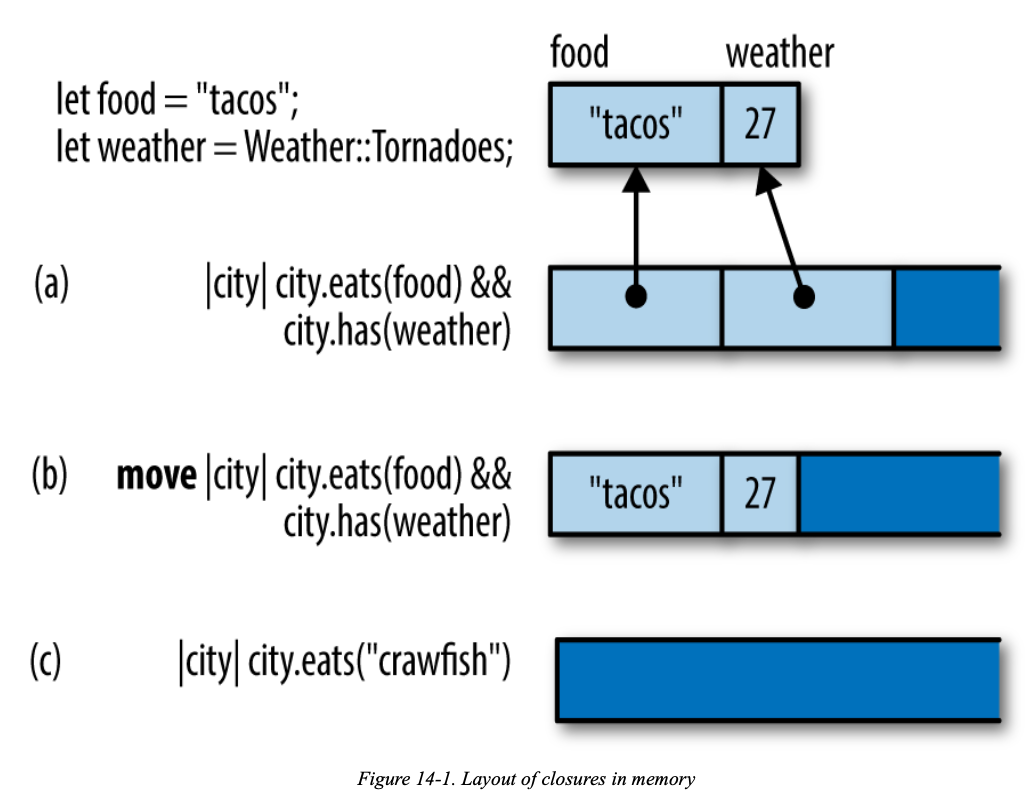

Capturing Variables

A closure can use data that belongs to an enclosing function.

| |

Closures That Borrow

In this case, when Rust creates the closure, it automatically borrows a reference to stat. It stands to reason: the closure refers to stat, so it must have a reference to it.

In short, Rust ensures safety by using lifetimes instead of garbage collection. Rust’s way is faster: even a fast GC allocation will be slower than storing stat on the stack, as Rust does in this case.

Closures That Steal

| |

The only thing we’ve changed is to add the move keyword before each of the two closures. The move keyword tells Rust that a closure doesn’t borrow the variables it uses: it steals them.

Rust thus offers two ways for closures to get data from enclosing scopes: moves and borrowing.

We get something important by accepting Rust’s strict rules: thread safety. It is precisely because the vector is moved, rather than being shared across threads, that we know the old thread won’t free the vector while the new thread is modifying it.

Function and Closure Types

| |

| |

| |

In fact, every closure you write has its own type, because a closure may contain data: values either borrowed or stolen from enclosing scopes. This could be any number of variables, in any combination of types. So every closure has an ad hoc type created by the compiler, large enough to hold that data. No two closures have exactly the same type. But every closure implements an Fn trait; the closure in our example implements Fn(&City) -> i64.

Closure Performance

As the figure shows, these closures don’t take up much space. But even those few bytes are not always needed in practice. Often, the compiler can inline all calls to a closure, and then even the small structs shown in this figure are optimized away.

Closures and Safety

Closures That Kill

| |

A closure that can be called only once may seem like a rather extraordinary thing, but we’ve been talking throughout this book about ownership and lifetimes. The idea of values being used up (that is, moved) is one of the core concepts in Rust. It works the same with closures as with everything else.

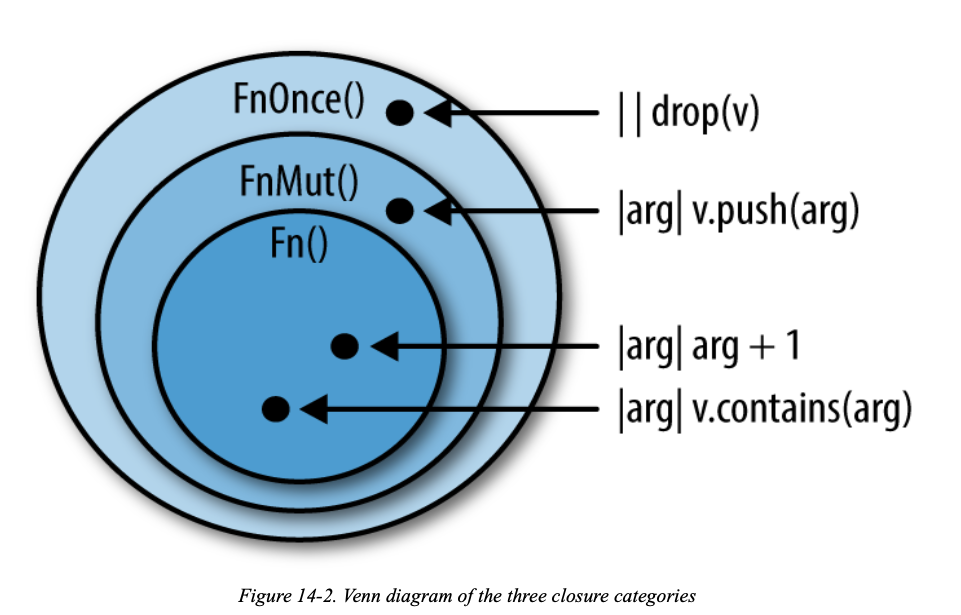

FnOnce