原文链接:Zero Knowledge Proofs: An illustrated primer。本篇文章通过图三色问题来介绍什么是零知识证明。

One of the best things about modern cryptography (密码学) is the beautiful terminology (术语). You could start any number of punk bands(朋克乐队) (or Tumblrs) named after cryptography terms like ‘hard-core predicate’, ‘trapdoor function’, ‘ or ‘impossible differential cryptanalysis (密码分析)’. And of course, I haven’t even mentioned the one term that surpasses all of these. That term is ‘zero knowledge‘.

In fact, the term ‘zero knowledge’ is so appealing(有吸引力的) that it leads to problems. People misuse it, assuming that zero knowledge must be synonymous(同义词) with ‘really, really secure‘. Hence it gets tacked(附加,增补) onto all kinds of stuff — like encryption(加密) systems and anonymity(匿名) networks — that really have nothing to do with true zero knowledge protocols.

澄清零知识的误区,像加密系统和匿名网络,真的和零知识协议没有关系。

This all serves to underscore a point: zero-knowledge proofs are one of the most powerful tools cryptographers have ever devised(设计的). But unfortunately they’re also relatively poorly understood. In this series of posts I’m going try to give a (mostly) non–mathematical description of what ZK proofs are, and what makes them so special. In this post and the next I’ll talk about some of the ZK protocols we actually use.

Origins of Zero Knowledge

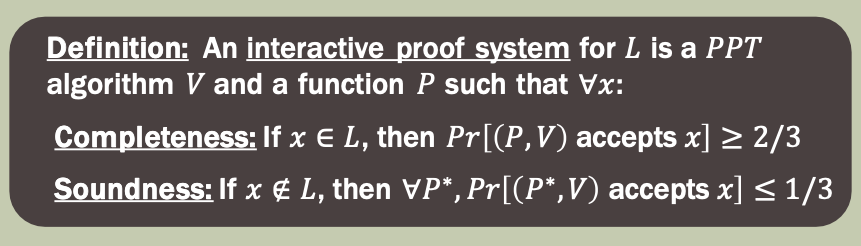

The notion of ‘zero knowledge’ was first proposed in the 1980s by MIT researchers Shafi Goldwasser, Silvio Micali and Charles Rackoff. These researchers were working on problems related to interactive proof systems, theoretical systems where a first party (called a ‘Prover’) exchanges messages with a second party (‘Verifier’) to convince the Verifier that some mathematical statement is true.*

零知识的概念出现在1980s Shafi Goldwasser,Silvio Micali 和 Charles Rackoff发表的这篇文章中。研究者关注在交互式证明系统,一方是“Prover”,另一方是“Verifier”,Prover与Verifier交换信息,来说服Verifier在数学上(可以是概率意义下)相信一些陈述是真的。

Prior to Goldwasser et al., most work in this area focused the soundness of the proof system. That is, it considered the case where a malicious(恶意的) Prover attempts to ‘trick’ a Verifier into believing a false statement. What Goldwasser, Micali and Rackoff did was to turn this problem on its head. Instead of worrying only about the Prover, they asked: what happens if you don’t trust the Verifier?

之前的工作主要考虑证明系统的可靠性,考虑的是恶意的证明方,而 Goldwasser, Micali 和 Rackoff 开始考虑如果不相信验证者会发生什么?我们不能傻乎乎的就把一些秘密泄漏给prover。

The specific concern they raised was information leakage. Concretely, they asked, how much extra information is the Verifier going to learn during the course of this proof, beyond the mere fact that the statement is true?

他们考虑的是验证者可能会泄漏信息,也就是在除了知道陈述是真的这个信息外,验证者通过这个证明过程还知道什么额外的信息?

It’s important to note that this is not simply of theoretical interest. There are real, practical applications where this kind of thing matters.

Here’s one: imagine that a real-world client wishes to log into a web server using a password. The standard ‘real world’ approach to this problem involves storing a hashed version of the password on the server. The login can thus be viewed as a sort of ‘proof’ that a given password hash is the output of a hash function on some password — and more to the point, that the client actually knows the password.

Most real systems implement this ‘proof’ in the absolute worst possible way. The client simply transmits the original password to the server, which re-computes the password hash and compares it to the stored value. The problem here is obvious: at the conclusion of the protocol, the server has learned my cleartext password. Modern password hygiene(卫生) therefore involves a good deal of praying that servers aren’t compromised(损害).

这里举了现实中的一个例子,就是密码登录。大多数实际的系统中客户端简单的将原始密码发送给服务端,服务端再计算一遍密码的哈希值,然后和存储的值进行比较。这里会出现安全问题,密码不泄漏只能祈祷于服务端不会出现问题。

What Goldwasser, Micali and Rackoff proposed was a new hope for conducting such proofs. If fully realized, zero knowledge proofs would allow us to prove statements like the one above, while provably revealing no information beyond the single bit of information corresponding to ‘this statement is true’.

零知识就是除了’this statement is true’外不会泄漏任何其他的信息。

A ‘real world’ example

So far this discussion has been pretty abstract. To make things a bit more concrete, let’s go ahead and give a ‘real’ example of a (slightly insane(疯狂的;非常愚蠢的)) zero knowledge protocol.

For the purposes of this example, I’d like you to imagine that I’m a telecom(电信) magnate(巨头) in the process of deploying(部署) a new cellular(蜂窝) communications network. My network structure is represented by the graph below. Each vertex(顶点) in this graph represents a cellular radio tower, and the connecting lines (edges) indicate locations where two cells overlap(重叠), meaning that their transmissions are likely to interfere with each other.

部署蜂窝网的例子,每个顶点代表一个蜂窝塔,每个边代表着两个有重叠,意味着他们之间的传输会相互影响。

This overlap is problematic, since it means that signals from adjacent towers are likely to scramble(争夺) reception. Fortunately my network design allows me to configure each tower to one of three different frequency bands to avoid such interference.

Thus the challenge in deploying my network is to assign frequency bands to the towers such that no two overlapping cells share the same frequencies. If we use colors to represent the frequency bands, we can quickly work out one solution to the problem:

两个相邻塔之间用不同的频率,也就转换为图三色问题。在计算复杂度分类上,它属于NP-complete问题。

Of course, many of you will notice that what I’m describing here is simply an instance of the famous theory problem called the graph three-coloring problem. You might also know that what makes this problem interesting is that, for some graphs, it can be quite hard to find a solution, or even to determine if a solution exists. **In fact, graph three-coloring — specifically, the decision problem of whether a given graph supports a solution with three colors — is known to be in the complexity class NP-complete.

It goes without saying that the toy example above is easy to solve by hand. But what if it wasn’t? For example, imagine that my cellular network was very large and complex, so much so that the computing power at my disposal(处理) was not sufficient to find a solution. In this instance, it would be desirable to outsource the problem to someone else who has plenty of computing power. For example, I might hire my friends at Google to solve it for me on spec.

But this leads to a problem.

Suppose that Google devotes a large percentage of their computing infrastructure to searching for a valid coloring for my graph. I’m certainly not going to pay them until I know that they really have such a coloring. At the same time, Google isn’t going to give me a copy of their solution until I’ve paid up. We’ll wind up at an impasse(僵局).

In real life there’s probably a common-sense answer to this dilemma, one that involves lawyers and escrow(第三方托管) accounts. But this is not a blog about real life, it’s a blog about cryptography. And if you’ve ever read a crypto paper, you’ll understand that the right way to solve this problem is to dream up an absolutely crazy technical solution.

A crazy technical solution (with hats!)

The engineers at Google consult with Silvio Micali at MIT, who in consultation with his colleagues Oded Goldreich and Avi Wigderson, comes up with the following clever protocol — one so elegant that it doesn’t even require any computers. All it requires is a large warehouse, lots of crayons(蜡笔), and plenty of paper. Oh yes, and a whole bunch of hats.**

Here’s how it works.

First I will enter the warehouse, cover the floor with paper, and draw a blank representation of my cell network graph. Then I’ll exit the warehouse. Google can now enter enter, shuffle a collection of three crayons to pick a random assignment of the three agreed-upon crayon colors (red/blue/purple, as in the example above), and color in the graph in with their solution. Note that it doesn’t matter which specific crayons they use, only that the coloring is valid.

Before leaving the warehouse, Google covers up each of the vertices with a hat. When I come back in, this is what I’ll see:

Obviously this approach protects Google’s secret coloring perfectly. But it doesn’t help me at all. For all I know, Google might have filled in the graph with a random, invalid solution. They might not even have colored the graph at all.

To address my valid concerns, Google now gives me an opportunity to ‘challenge’ their solution to the graph coloring*.* I’m allowed to pick — at random — a single ‘edge’ of this graph (that is, one line between two adjacent hats). Google will then remove the two corresponding hats, revealing a small portion of their solution:

Notice that there are two outcomes to my experiment:

- If the two revealed vertices are the same color (or aren’t colored in at all!) then I definitely know that Google is lying to me. Clearly I’m not going to pay Google a cent.

- If the two revealed vertices are different colors, then Google might not be lying to me.

Hopefully the first proposition is obvious. The second one requires a bit more consideration. The problem is that even after our experiment, Google could still be lying to me — after all, I only looked under two of the hats. If there are E different edges in the graph, then Google could fill in an invalid solution and still get away with it most of the time. Specifically, after one test they could succeed in cheating me with probability up to (E-1)/E (which for a 1,000 edge graph works out to 99.9% of the time).

Fortunately Google has an answer to this. We’ll just run the protocol again!

We put down fresh paper with a new, blank copy of the graph. Google now picks a new (random) shuffle of the three crayons. Next they fill in the graph with a valid solution, but using the new random ordering of the three colors.

The hats go back on. I come back in and repeat the challenge process, picking a new random edge. Once again the logic above applies. Only this time if all goes well, I should now be slightly more confident that Google is telling me the truth. That’s because in order to cheat me, Google would have had to get lucky twice in a row. That can happen — but it happens with relatively lower probability. The chance that Google fools me twice in a row is now (E-1)/*E ** (E-1)/E (or about 99.8% probability for our 1,000 edge example above).

Fortunately we don’t have to stop at two challenges. In fact, we can keep trying this over and over again until I’m confident that Google is probably telling me the truth.

But don’t take my word for it. Thanks to some neat Javascript, you can go try it yourself.

Note that I’ll never be perfectly certain that Google is being honest — there’s always going to be a tiny probability that they’re cheating me. But after a large number of iterations (E^2, as it happens) I can eventually raise my confidence to the point where Google can only cheat me with negligible probability — low enough that for all practical purposes it’s not worth worrying about. And then I’ll be able to safely hand Google my money.

What you need to believe is that Google is also protected. Even if I try to learn something about their solution by keeping notes between protocol runs, it shouldn’t matter. I’m foiled by Google’s decision to randomize their color choices between each iteration. The limited information I obtain does me no good, and there’s no way for me to link the data I learn between interactions.

总结一下上面的过程,首先我进入房间,画出图,接着Google进入房间,随机选择三种颜色,涂上解法,盖上帽子,最后我再进入房间,取下任意一个边的两个帽子,看是否是相同颜色。重复上述过程足够多次,$E^2$次,有理由相信Google有解,而我无法通过这个交互过程获得解的信息。

What makes it ‘zero knowledge’?

I’ve claimed to you that this protocol leaks no information about Google’s solution. But don’t let me get away with this! The first rule of modern cryptography is never to trust people who claim such things without proof.

Goldwasser, Micali and Rackoff proposed three following properties that every zero-knowledge protocol must satisfy. Stated informally, they are:

- Completeness. If Google is telling the truth, then they will eventually convince me (at least with high probability).

- Soundness. Google can only convince me if they’re actually telling the truth.

- Zero-knowledgeness. (Yes it’s really called this.) **I don’t learn anything else **about Google’s solution.

零知识协议需要满足:

- 完备性。如果Google说的是事实,那么他们最终会说服我。

- 可靠性。只有当Google真的说的是事实时才能说服我。

- 零知识。我不能获得关于Google 解法的任何知识。

We’ve already discussed the argument for completeness. The protocol will eventually convince me (with a negligible error probability), provided we run it enough times. Soundness is also pretty easy to show here. If Google ever tries to cheat me, I will detect their treachery with overwhelming probability.

完备性证明:上述过程已经证明了,只要交互过程重复的次数足够多,最终都会以一个可以忽略的错误概率来使我信服。

可靠性证明:如果Google欺骗我,我会有压倒性的概率发现这一点。

参考BIU课程,完备性和可靠性的严格定义。

The hard part here is the ‘zero knowledgeness’ property. To do this, we need to conduct a very strange thought experiment.

A thought experiment (with time machines)

First, let’s start with a crazy hypothetical(假设). Imagine that Google’s engineers aren’t quite as capable as people make them out to be. They work on this problem for weeks and weeks, but they never manage to come up with a solution. With twelve hours to go until showtime, the Googlers get desperate. They decide to trick me into thinking they have a coloring for the graph, even though they don’t.

Their idea is to sneak into the GoogleX workshop and borrow Google’s prototype time machine. Initially the plan is to travel backwards a few years and use the extra working time to take another crack at solving the problem. Unfortunately it turns out that, like most Google prototypes, the time machine has some limitations. Most critically: it’s only capable of going backwards in time four and a half minutes.

So using the time machine to manufacture more working time is out. But still, it turns out that even this very limited technology can still be used to trick me.

I don’t really know what’s going on herebut it seemed apropos.

The plan is diabolically(非常) simple. Since Google doesn’t actually know a valid coloring for the graph, they’ll simply color the paper with a bunch of random colors, then put the hats on. If by sheer luck, I challenge them on a pair of vertices that happen to be different colors, everyone will heave a sigh of relief and we’ll continue with the protocol. So far so good.

Inevitably(不可避免地), though, I’m going to pull off a pair of hats and discover two vertices of the same color. In the normal protocol, Google would now be totally busted(崩溃). And this is where the time machine comes in. Whenever Google finds themselves in this awkward situation, they simply fix it. That is, a designated Googler pulls a switch, ‘rewinds’ time about four minutes, and the Google team recolors the graph with a completely new random solution. Now they let time roll forward and try again.

In effect, the time machine allows Google to ‘repair’ any accidents that happen during their bogus(虚假的) protocol execution, which makes the experience look totally legitimate to me. Since bad challenge results will occur only 1/3 of the time, the expected runtime of the protocol (from Google’s perspective) is only moderately greater than the time it takes to run the honest protocol. From my perspective I don’t even know that the extra time machine trips are happening.

This last point is the most important. In fact, from my perspective, being unaware that the time machine is in the picture, the resulting interaction is exactly the same as the real thing. It’s statistically identical. And yet it’s worth pointing out again that in the time machine version, Google has absolutely no information about how to color the graph.

总结一下,Google不知道图涂色的解法,但是他们有神器时间机器,可以倒退四分半的时间。 如果在交互过程中失败,他们就使用时间机器倒退,重新涂色。 从我的角度来看,我没有意识到他们有时间机器,因此产生的互动和真实的东西完全一样,在统计上是相同的。但是在时间机器版本,Google完全没有涂色的解法。

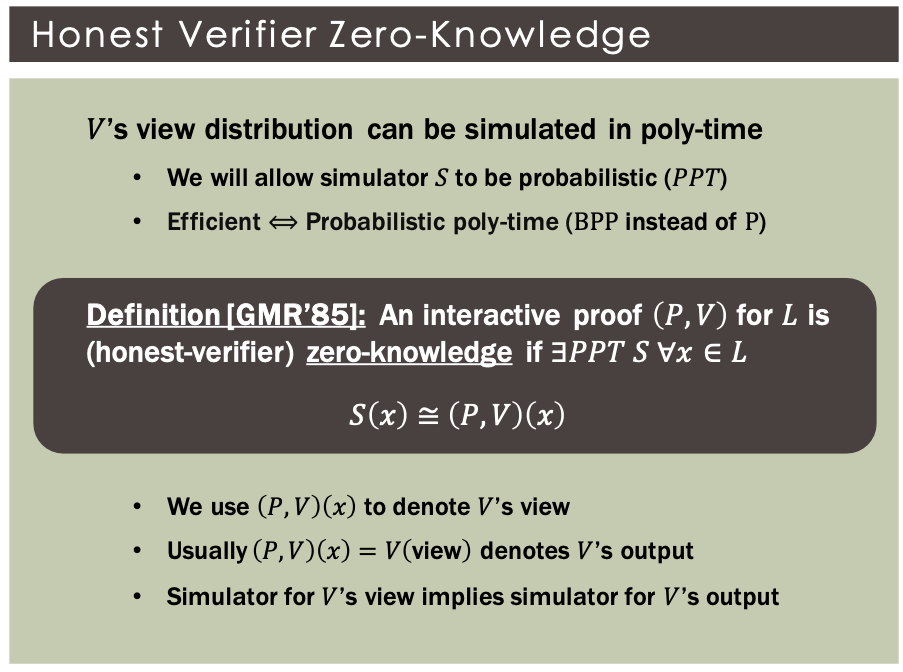

BIU课程中对HVZK的定义:

What the hell is the point of this?

What we’ve just shown is an example of a simulation. Note that in a world where time runs only forward and nobody can trick me with a time machine, the hat-based protocol is correct and sound, meaning that after E^2 rounds I should be convinced (with all but negligible probability) that the graph really is colorable and that Google is putting valid inputs into the protocol.

What we’ve just shown is that if time doesn’t run only forward — specifically, if Google can ‘rewind’ my view of time — then they can fake a valid protocol run even if they have no information at all about the actual graph coloring.

From my perspective, what’s the difference between the two protocol transcripts? When we consider the statistical distribution of the two, there’s no difference at all*.* Both convey exactly the same amount of useful information.

Believe it or not, this proves something very important.

Specifically, assume that I (the Verifier) have some strategy that ‘extracts’ useful information about Google’s coloring after observing an execution of the honest protocol. Then my strategy should work equally well in the case where I’m being fooled with a time machine. The protocol runs are, from my perspective, statistically identical. I physically cannot tell the difference.

Thus if the amount of information I can extract is identical in the ‘real experiment’ and the ‘time machine experiment’, yet the amount of information Google puts into the ‘time machine’ experiment is exactly zero — then this implies that even in the real world the protocol must not leak any useful information.

Thus it remains only to show that computer scientists have time machines. We do! (It’s a well-kept secret.)

总结:从我的视角来看,两个协议是没有区别的,因为它们在统计上的分布是相同的,它们都传达了完全相同数量的有用信息。 具体来说,如果我能在真实世界中提取一些有用的信息,那么我在时间机器版本中也能提取有用的信息,但是由于时间机器实验中的信息量为0,因此也就意味着即使是在现实世界,协议也不会泄漏任何有用的信息。 因此,我们知道计算机科学家拥有时间机器。

Getting rid of the hats (and time machines)

Of course we don’t actually want to run a protocol with hats. And even Google (probably?) doesn’t have a literal time machine.

To tie things together, we first need to bring our protocol into the digital world. This requires that we construct the digital equivalent of a ‘hat’: something that both hides a digital value, while simultaneously ‘binding’ (or ‘committing’) the maker to it, so she can’t change her mind after the fact. 这里说的就是binding性质,揭露之后值就固定下来了。

Fortunately we have a perfect tool for this application. It’s called a digital commitment scheme. A commitment scheme allows one party to ‘commit’ to a given message while keeping it secret, and then later ‘open’ the resulting commitment to reveal what’s inside. They can be built out of various ingredients(组成部分), including (strong) cryptographic hash functions.******

这里给出了一个数字 commitment scheme。

Given a commitment scheme, we now have all the ingredients we need to run the zero knowledge protocol electronically. The Prover first encodes its vertex colorings as a set of digital messages (for example, the numbers 0, 1, 2), then generates digital commitments to each one. These commitments get sent over to the Verifier. When the Verifier challenges on an edge, the Prover simply reveals the opening values for the commitments corresponding to the two vertices.

其实就是用数字的commitment来代替之前物理上的帽子。

So we’ve managed to eliminate the hats. But how do we prove that this protocol is zero knowledge?

Fortunately now that we’re in the digital world, we no longer need a real time machine to prove things about this protocol. A key trick is to specify in our setting that the protocol is not going to be run between two people, but rather between two different computer programs (or, to be more formal, probabilistic Turing machines.)

What we can now prove is the following theorem: if you could ever come up with a computer program (for the Verifier) that extracts useful information after participating in a run of the protocol, then it would be possible to use a ‘time machine’ on that program in order to make it extract the same amount of useful information from a ‘fake’ run of the protocol where the Prover doesn’t put in any information to begin with.

And since we’re now talking about computer programs, it should be obvious that rewinding time isn’t such an extraordinary feat at all. In fact, we rewind computer programs all the time. For example, consider using virtual machine software with a snapshot capability.

Example of rewinding through VM snapshots. An initial VM is played forward, rewound to aninitial snapshot, then execution is forked to a new path.

Even if you don’t have fancy virtual machine software, any computer program can be ‘rewound’ to an earlier state, simply by starting the program over again from the beginning and feeding it exactly the same inputs. Provided that the inputs — including all random numbers — are fixed, the program will always follow the same execution path. Thus you can rewind a program just by running it from the start and ‘forking’ its execution when it reaches some desired point.

Ultimately what we get is the following theorem. If there exists any Verifier computer program that successfully extracts information by interactively running this protocol with some Prover, then we can simply use the rewinding trick on that program to commit to a random solution, then ‘trick’ the Verifier by rewinding its execution whenever we can’t answer its challenge correctly. The same logic holds as we gave above: if such a Verifier succeeds in extracting information after running the real protocol, then it should be able to extract the same amount of information from the simulated, rewinding-based protocol. But since there’s no information going into the simulated protocol, there’s no information to extract. Thus the information the Verifier can extract must always be zero.

Ok, so what does this all mean?

So let’s recap. We know that the protocol is complete and sound, based on our analysis above. The soundness argument holds in any situation where we know that nobody is fiddling(无足轻重地) with time — that is, the Verifier is running normally and nobody is rewinding its execution.

At the same time, the protocol is also zero knowledge. To prove this, we showed that any Verifier program that succeeds in extracting information must also be able to extract information from a protocol run where rewinding is used and no information is available in the first place. Which leads to an obvious contradiction(矛盾), and tells us that the protocol can’t leak information in either situation.

同时协议也是零知识的。为了证明这一点,我们已经展示了任何能够成功提取信息的验证程序也必须在使用了rewinding超能力的协议中成功提取信息,但是这个协议是不能获取到任何知识的。这也就告诉了我们在这两种情况下都没有泄漏知识。

There’s an important benefit to all this. Since it’s trivial for anyone to ‘fake’ a protocol transcript, even after Google proves to me that they have a solution, I can’t re-play a recording of the protocol transcript to prove anything to anyone else (say, a judge). That’s because the judge would have no guarantee that the video was recorded honestly, and that I didn’t simply edit in the same way Google might have done using the time machine. This means that protocol transcripts themselves contain no information. The protocol is only meaningful if I myself participated, and I can be sure that it happened in real time.

模拟的和真实的是无法在真实世界中进行区分的,所以只有当我参与进去的时候,协议才是有意义的,并且我能确保实在真实时间中发生的。

Proofs for all of NP!

If you’ve made it this far, I’m pretty sure you’re ready for the big news. Which is that 3-coloring cellphone networks isn’t all that interesting of a problem — at least, not in and of itself.

The really interesting thing about the 3-coloring problem is that it’s in the class NP-complete. To put this informally, the wonderful thing about such problems is that any other problem in the class NP can be translated into an instance of that problem.In a single stroke, this result — due to Goldreich, Micali and Wigderson — proves that ‘efficient’ ZK proofs exists for a vast class of useful statements, many of which are way more interesting than assigning frequencies to cellular networks. You simply find a statement (in NP) that you wish to prove, such as our hash function example from above, then translate it into an instance of the 3-coloring problem. At that point you simply run the digital version of the hat protocol.

三涂色问题是NPC问题,那么对于一个想要证明的NP问题,都可以归约到这个NPC问题,然后转化成三涂色问题,用上面的数字协议进行运行就可以了。

In summary, and next time

Of course, actually running this protocol for interesting statements would be an insanely(疯狂地) silly thing for anyone to do, since the cost of doing so would include the total size of the original statement and witness, plus the reduction cost to convert it into a graph, plus the $E^2$ protocol rounds you’d have to conduct in order to convince someone that the proof is valid. Theoretically this is ‘efficient’, since the total cost of the proof would be polynomial in the input size, but in practice it would be anything but.

理论上上面的三色问题的零知识证明协议是“efficent”,但是不实用。

So what we’ve shown so far is that such proofs are possible. It remains for us to actually find proofs that are practical enough for real-world use.

In the next post I’ll talk about some of those — specifically, the efficient proofs that we use for various useful statements. I’ll give some examples (from real applications) where these things have been used. Also at reader request: I’ll also talk about why I dislike SRP so much.

See here for Part 2.

Notes:

- Formally, the goal of an interactive proof is to convince the Verifier that a particular string belongs to some language. Typically the Prover is very powerful (unbounded), but the Verifier is limited in computation.

*This example is based on the original solution of Goldwasser, Micali and Rackoff, and the teaching example using hats is based on an explanation by Silvio Micali. I take credit only for the silly mistakes.- ***** A simple example of a commitment can be built using a hash function. To commit to the value “x” simply generate some (suitably long) string of random numbers, which we’ll call ‘salt’, and output the commitment C = Hash(salt || x). To open the commitment, you simply reveal ‘x’ and ‘salt’. Anyone can check that the original commitment is valid by recomputing the hash. This is secure under some (moderately strong) assumptions about the function itself.