原文链接:Zero Knowledge Proofs: An illustrated primer, Part 2。这篇博客通过Schnorr协议详细讲解了零知识证明中的完备性、可靠性以及零知识,对于弄懂提取器、模拟器以及零知识等概念很有帮助。之前对于模拟器的作用有些懵懵懂懂,现在看完后有一种透彻的感觉😃。

📝 总结一下:

任何零知识证明必须满足三个重要的性质:

- 完备性。任何诚实的Prover最终都能够使Verifier信服。

- 可靠性。如果能说服Verifier,那么一定有命题是真的。逆否命题就是,如果命题不为真,那么就不能说服Verifier。

- 零知识。Verifier除了知道命题为真外不能获得其他任何信息。

如何在证明可靠性和零知识性质的同时又不会泄漏知识呢?秘诀就是模拟器,模拟器中拥有在实际中不可能有的超能力,比如说时间机器。这样就很巧妙的解决了这个问题!

证明可靠性,使用模拟器!可靠性说的是如果能说服Verifier,那么一定有命题为真。博客中主要讨论的"statement"是个人知识而不是"facts",也就是“我知道某个知识,或者说秘密吧”。具体来讲,可靠性就变成了,如果能说服Verifier,那么Prover一定是知道知识的。为了证明这一点,搬出提取器的概念,提取器充当Verifier的角色,对于任何可能的Prover,如果都存在一个提取器能够提取到知识,那么就说明Prover肯定是有知识的。这不就证明了可靠性嘛!

那问题是提取器怎么提取知识呢?让我们上模拟器中的超能力——时光机器!提取器能够回溯,达到骗Prover在两次运行中使用相同的随机数$k$,然后计算出Prover原来拥有的密钥$a$。

证明零知识,使用模拟器!要证明现实中的Verifier除了知道Prover知道知识这一点外不能获取到其他任何信息,我们构造一个压根就不知道密钥$a$的Prover,它和诚实的Verifier交互,让Verifier相信Prover是知道密钥$a$的。同时在统计意义上,模拟器中交互的输出分布和真实Prover和Verifier交互的输出分布是一样的。那么由于模拟器中根本没有知识,也就证明了零知识。

那么如何在模拟器中让Prover说服Verifier呢?上超能力——时光机器!Prover先发一个初始值$g^{k_1}$骗取到Verifier的随机数$c$,回溯Verifier,让它发送随机数$z$,进行一些计算得到初始值,当Verifier发起随机挑战$c$时,Prover输出$z$就能让Verifier相信Prover知道密钥$a$,实际上Prover不知道密钥$a$。

上面的过程都是交互的,转换成非交互零知识证明的一个方式是用可靠的哈希函数来发起随机挑战。

好的!下面开始边读博客文章边做笔记。👇

This post is the second in a two-part series on zero-knowledge proofs. Click here to read Part 1.

In this post I’m going to continue the short, (relatively) non-technical overview of zero knowledge proofs that I started a couple of years ago. Yes, that was a very long time! If you didn’t catch the first post, now would be an excellent time to go read it.

Before we go much further, a bit of a warning. While this series is still intended as a high-level overview, at a certain point it’s necessary to dig a bit deeper into some specific algorithms. So you should expect this post to get a bit wonkier than the last.

A quick recap, and a bit more on Zero Knowledge(ness)

First, a brief refresher.

In the last post we defined a zero knowledge proof as an interaction between two computer programs (or Turing machines) — respectively called a Prover and a Verifier — where the Prover works to convince the Verifier that some mathematical statement is true. We also covered a specific example: a clever protocol by Goldreich, Micali and Wigderson that allows us to prove, in zero knowledge, that a graph possesses a three-coloring.

In the course of that discussion, we described three critical properties that any zero knowledge proof must satisfy:

- Completeness: If the Prover is honest, then she will eventually convince the Verifier.

- Soundness: The Prover can only convince the Verifier if the statement is true.

- Zero-knowledge(ness): The Verifier learns no information beyond the fact that the statement is true.

The real challenge turns out to be finding a way to formally define the last property. How do you state that a Verifier learns nothing beyond the truth of a statement?

In case you didn’t read the previous post — the answer to this question came from Goldwasser, Micali and Rackoff, and it’s very cool. What they argued is that a protocol can be proven zero knowledge if for every possible Verifier, you can demonstrate the existence of an algorithm called a ‘Simulator’, and show that this algorithm has some very special properties.

From a purely mechanical perspective, the Simulator is like a special kind of Prover. However, unlike a real Prover — which starts with some special knowledge that allows it to prove the truth of a statement — the Simulator gets no special knowledge at all.* Nonetheless, the Simulator (or Simulators) must be able to ‘fool’ every Verifier into believing that the statement is true, while producing a transcript that’s statistically identical top (or indistinguishable from) the output of a real Prover.

上面关于模拟器的叙述比较重要。可以将模拟器看作是特殊的一种Prover。模拟器必须可以骗过任何的Verifier相信命题是真的,而且模拟器产生的结果和与一个真实的Prover交互得到的结果在统计上是不可区分的。

The logic here flows pretty cleanly: since Simulator has no ‘knowledge’ to extract in the first place, then clearly a Verifier can’t obtain any meaningful amount of information after interacting with it. Moreover, if the transcript of the interaction is distributed identically to a real protocol run with a normal Prover, then the Verifier can’t do better against the real prover than it can do against the Simulator. (If the Verifier could do better, then that would imply that the distributions were not statistically identical.) Ergo, the Verifier can’t extract useful information from the real protocol run.

This is incredibly wonky, and worse, it seems contradictory! We’re asking that a protocol be both sound — meaning that a bogus(虚假的) Prover can’t trick some Verifier into accepting a statement unless it has special knowledge allowing it to prove the statement — but we’re also asking for the existence of an algorithm (the simulator) that can literally cheat. Clearly both properties can’t hold at the same time.

The solution to this problem is that both properties don’t hold at the same time.

To build our simulator, we’re allowed to do things to the Verifier that would never happen in the real world. The example that I gave in the previous post was to use a ‘time machine’ — that is, our ‘Simulator’ can rewind the Verifier program’s execution in order to ‘fool’ it. Thus, in a world where we can wind the Verifier back in time, it’s easy to show that a Simulator exists. In the real world, of course it doesn’t. This ‘trick’ gets us around the contradiction.

看似模拟器没有知识也能骗过Verifier和Prover除非有知识才能通过Verifier的测验是矛盾的,但其实这两个不是同时成立的。模拟器有一些真实世界没有的超能力,比如说时间机器,这样模拟器是可以骗过Verifier的。

As a last reminder, to illustrate all of these ideas, we covered one of the first general zero knowledge proofs, devised by Goldreich, Micali and Wigderson (GMW). That protocol allowed us to prove, in zero knowledge, that a graph supports a three-coloring. Of course, proving three colorings isn’t terribly interesting. The real significance of the GMW result is theoretical. Since graph three coloring is known to be in the complexity class NP-complete, the GMW protocol can be used to prove any statement in the class NP. And that’s quite powerful.

Let me elaborate slightly on what that means:

- If there exists any decision problem (that is, a problem with a yes/no answer) whose witness (solution) can be verified in polynomial time, then:

- We can prove that said solution exists by (1) translating the problem into an instance of the graph three-coloring problem, and (2) running the GMW protocol.*

This amazing result gives us interactive zero knowledge proofs for every statement in NP. The only problem is that it’s almost totally unusable.

我们知道GMW中的图三色问题是NPC问题,而NP问题可以归约成图三色问题,然后可以用GMW协议来进行零知识证明。唯一的问题是这是不实用的。

From theory into practice

If you’re of a practical mindset, you’re probably shaking your head at all this talk of ZK proofs. That’s because actually using this approach would be an insanely expensive and stupid thing to do. Most likely you’d first represent your input problem as a boolean circuit where the circuit is satisfied if and only if you know the correct input. Then you’d have to translate your circuit into a graph, resulting in some further blowup. Finally you’d need to run the GMW protocol, which is damned expensive all by itself.

So in practice nobody does this. It’s really considered a ‘feasibility’(可行性) result. Once you show that something is possible, the next step is to make it efficient.

But we do use zero knowledge proofs, almost every day. In this post I’m going to spend some time talking about the more practical ZK proofs that we actually use. To do that I just need give just a tiny bit of extra background.

Proofs vs. Proofs of Knowledge

Before we go on, there’s one more concept we need to cover. Specifically, we need to discuss what precisely we’re proving when we conduct(执行) a zero knowledge proof*.*Let me explain. At a high level, there are two kinds of statement you might want to prove in zero knowledge. Roughly speaking, these break up as follows.

Statements about “facts”. For example, I might wish to prove that “a specific graph has a three coloring” or “some number N is in the set of composite numbers“. Each of these is a statement about some intrinsic property of the universe.

Statements about my personal knowledge. Alternatively, I might wish to prove that I know some piece information. Examples of this kind of statement include: “I know a three coloring for this graph”, or “I know the factorization of N”. These go beyond merely proving that a fact is true, and actually rely on what the Prover knows.

陈述的命题有两种,一种是事实,一种是个人的知识。在这篇博客中,主要关注在第二种命题。

It’s important to recognize that there’s a big difference between these two kinds of statements! For example, it may be possible to prove that a number N is composite even if you don’t know the full factorization. So merely proving the first statement is not equivalent to proving the second one.

The second class of proof is known as a “proof of knowledge”. It turns out to be extremely useful for proving a variety of statements that we use in real life. In this post, we’ll mostly be focusing on this kind of proof.

The Schnorr identification protocol

Now that we’ve covered some of the required background, it’s helpful to move on to a specific and very useful proof of knowledge that was invented by Claus-Peter Schnorr in the 1980s. At first glance, the Schnorr protocol may seem a bit odd, but in fact it’s the basis of many of our modern signature schemes today.

Schnorr wasn’t really concerned with digital signatures, however. His concern was with identification. Specifically, let’s imagine that Alice has published her public key to the world, and later on wants to prove that she knows the secret key corresponding to that public key. This is the exact problem that we encounter in real-world protocols such as public-key SSH, so it turns out to be well-motivated.

Schnorr began with the assumption that the public key would be of a very specific format. Specifically, let p be some prime number, and let g be a generator of a cyclic group(循环群) of prime-order q. To generate a keypair, Alice would first pick a random integer a between 1 and q, and then compute the keypair as:

$PK_A=g^a\mod p,SK_A = a$

(If you’ve been around the block a time or two, you’ll probably notice that this is the same type of key used for Diffie-Hellman and the DSA signing algorithm. That’s not a coincidence, and it makes this protocol very useful.)

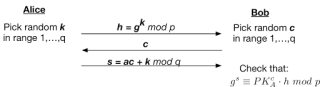

Alice keeps her secret key to herself, but she’s free to publish her public key to the world. Later on, when she wants to prove knowledge of her secret key, she conducts the following simple interactive protocol with Bob:

There’s a lot going on in here, so let’s take a minute to unpack things.

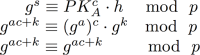

First off, we should ask ourselves if the protocol is complete. This is usually the easiest property to verify: if Alice performs the protocol honestly, should Bob be satisfied at the end of it? In this case, completeness is pretty easy to see just by doing a bit of substitution:

注意,由于选取的$k \in { 1, \dots, q }$,因此$k\mod q = k$。

这里证明了完备性:诚实的Alice是能够说服Bob的。

Proving soundness

The harder property is soundness. Mainly because we don’t yet have a good definition of what it means for a proof of knowledge to be sound. Remember that what we want to show is the following:

If Alice successfully convinces Bob, then she must know the secret key a.

可靠性:如果Alice能够成功让Bob信服,那么她一定知道密钥$a$。也就是说如果Alice不是诚实的,她不知道密钥$a$的话,那么她肯定不能说服Bob。

It’s easy to look at the equations above and try to convince yourself that Alice’s only way to cheat the protocol is to know a. But that’s hardly a proof.

When it comes to demonstrating the soundness of a proof of knowledge, we have a really nice formal approach. Just as with the Simulator we discussed above, we need to demonstrate the existence of a special algorithm. This algorithm is called a knowledge extractor, and it does exactly what it claims to. A knowledge extractor (or just ‘Extractor’ for short) is a special type of Verifier that interacts with a Prover, and — if the Prover succeeds in completing the proof — the Extractor should be able to extract the Prover’s original secret.

想要证明可靠性,借助于知识提取器来证明。一个知识提取器是一个特殊的Verifier,它和Prover进行交互,如果Prover能成功通过证明,那么提取器可以提取到Prover原来的密码。

And this answers our question above. To prove soundness for a proof of knowledge, we must show that an Extractor exists for every possible Prover.

为了证明可靠性,我们现在必须证明对于每一个可能的Prover,都存在这样一个提取器。结合上面提到的可靠性陈述,如果Alice能够成功让Bob信服,那么她一定知道密钥$a$。也就是说,如果对于每一个可能让Bob信服的Alice,如果存在一个知识提取器来与Alice交互,能提取到密钥$a$,不就说明了Alice肯定知道密钥$a$嘛!因此证明了可靠性。

证明逻辑是:对每一个可能的Prover存在一个提取器 ⇒ 如果Alice能让Bob信服,Alice一定知道原来的秘密(可靠性)

Of course this again seems totally contradictory to the purpose of a zero knowledge protocol — where we’re not supposed to be able to learn secrets from a Prover. Fortunately we’ve already resolved this conundrum once for the case of the Simulator. Here again, we take the same approach. The Extractor is not required to exist during a normal run of the protocol. We simply show that it exists if we’re allowed to take special liberties with the Prover — in this case, we’ll use ‘rewinding’ to wind back the Prover’s execution and allow us to extract secrets.

当然这看起来又和零知识证明协议的目的冲突了,但是我们依然可以用模拟器的方法来解决这个问题。我们只需要让Prover拥有超能力,然后这样的提取器是存在的。这个超能力可以是时间机器,肯定现实世界不存在时间机器,因此不会和泄漏知识这个目的相冲突。

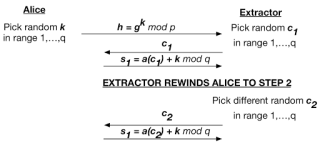

The extractor for the Schnorr protocol is extremely clever — and it’s also pretty simple. Let’s illustrate it in terms of a protocol diagram. Alice (the Prover) is on the left, and the Extractor is on the right:

The key observation here is that by rewinding Alice’s execution, the Extractor can ‘trick’ Alice into making two different proof transcripts using the same k. This shouldn’t normally happen in a real protocol run, where Alice specifically picks a new k for each execution of the protocol.

关键的一点是通过让Alice重新执行到第2步,提取器可以骗Alice给两个不同的证明但是用同一个$k$。在实际的协议运行中,这是通常不应该发生的,Alice会在协议每次执行的时候特别选择一个新的$k$。

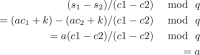

If the Extractor can trick Alice into doing this, then he can solve the following simple equation to recover Alice’s secret:

如果提取器能够骗Alice这样做的话,提取器是可以提取到Alice拥有的密钥$a$。

推导的详细过程:

$$ \begin{array}{l} \frac{s_1 - s_2}{c_1 - c_2} \mod q & \\\ \quad = \frac{((ac_1+k) \mod q)-((ac_2 + k) \mod q)}{c_1 - c_2} \mod q \\\ \quad = \frac{(ac_1+k)-(ac_2 + k) }{c_1 - c_2} \mod q \\\ \quad = \frac{ac_1 - ac_2 }{c_1 - c_2} \mod q \\\ \quad = a \mod q \end{array} $$It’s worth taking a moment right now to note that this also implies a serious vulnerability(漏洞) in bad implementations of the Schnorr protocol. If you ever accidentally use the same k for two different runs of the protocol, an attacker may be able to recover your secret key! This can happen if you use a bad random number generator.

需要注意Schnorr protocol在实际中可能出现的漏洞,那就是在不同运行中使用相同的$k$,因此要选择好的随机生成器。

Indeed, those with a bit more experience will notice that this is similar to a *real* attack on systems (with bad random number generators) that implement ECDSA or DSA signatures! This is also not a coincidence. The (EC)DSA signature family is based on Schnorr. Ironically(讽刺地), the developers of DSA managed to retain this vulnerability of the Schorr family of protocols while at the same time ditching the security proof that makes Schnorr so nice.

Proving zero-knowledge(ness) against an honest Verifier

Having demonstrated(证明) that Schnorr signatures are complete and sound, it remains only to prove that they’re ‘zero knowledge’. Remember that to do this, normally we require a Simulator that can interact with any possible Verifier and produce a ‘simulated’ transcript of the proof, even if the Simulator doesn’t know the secret it’s proving it knows.

为了证明“零知识”,一般要求有一个可以和所有可能的Verifier的模拟器,输出证明的结果,而模拟器甚至不知道它要证明的知识。

The standard Schnorr protocol does not have such a Simulator, for reasons we’ll get into in a second. Instead, to make the proof work we need to make a special assumption. Specifically, the Verifier needs to be ‘honest’. That is, we need to make the special assumption that it will run its part of the protocol correctly — namely, that it will pick its challenge “c” using only its random number generator, and will not choose this value based on any input we provide it. As long as it does this, we can construct a Simulator.

标准的Schnorr协议是没有这样的模拟器的。这里要做一个假设,Verifier需要是“诚实的”。我们需要假设在Verifier选择挑战“c”时,只用到一个随机数生成器,而不会选择那些基于任何我们提供的输入生成的值。

Here’s how the Simulator works.

Let’s say we are trying to prove knowledge of a secret $a$ for some public key $g^a \mod p$ — but we don’t actually know the value*.* Our Simulator assumes that the Verifier will choose some value $c$ as its challenge, and moreover, it knows that the honest Verifier will choose the value $c$ only based on its random number generator — and not based on any inputs the Prover has provided.

- First, output some initial $g^{k_1}$ as the Prover’s first message*,* and find out what challenge $c$ the Verifier chooses.

- Rewind the Verifier, and pick a random integer $z$ in the range ${ 0, \cdots, q-1 }$.

- Compute $g^{k_2} = g^z * g^{a(-c)}$ **and output $g^{k_2}$ as the Prover’s new initial message.

- When the Verifier challenges on $c$ again, output $z$.

Notice that the transcript $g^k,c,z$ will verify correctly as a perfectly valid, well-distributed proof of knowledge of the value $a$. The Verifier will accept this output as a valid proof of knowledge of $a$, even though the Simulator does not know $a$ in the first place!

详细的过程如下:

What this proves is that if we can rewind a Verifier, then (just as in the first post in this series) we can always trick the Verifier into believing we have knowledge of a value, even when we don’t. And since the statistical distribution of our protocol is identical to the real protocol, this means that our protocol must be zero knowledge — against an honest Verifier.

在模拟器世界里,我们可以回溯Verifier,让诚实的Verifier相信我们是知道密钥$a$的,但其实我们根本不知道$a$时多少。由于在统计分布上我们的协议和真实的协议是一样的,那么对于诚实的Verifier,我们的协议一定是零知识的。

From interactive to non-interactive

So far we’ve shown how to use the Schnorr protocol to interactively prove knowledge of a secret key $a$ that corresponds to a public key $g^a$. This is an incredibly useful protocol, but it only works if our Verifier is online and willing to interact with us.

An obvious question is whether we can make this protocol work without interaction. Specifically, can I make a proof that I can send you without you even being online. Such a proof is called a non-interactive zero knowledge proof (NIZK). Turning Schnorr into a non-interactive proof seems initially quite difficult — since the protocol fundamentally relies on the Verifier picking a random challenge. Fortunately there is a clever trick we can use.

This technique was developed by Fiat and Shamir in the 1980s. What they observed was that if you have a decent hash function lying around, you can convert an interactive protocol into a non-interactive one by simply using the hash function to pick the challenge.

怎么将交互式零知识证明转换成非交互式零知识证明呢?转换的难点在于Verifier需要选择一个随机的挑战,一个解决方法是使用可靠的哈希函数来选择这个挑战。

Specifically, the revised protocol for proving knowledge of $a$ with respect to a public key $g^k$ looks like this:

- The Prover picks $g^k$ (just as in the interactive protocol).

- Now, the prover computes the challenge as $c = H(g^k||M)$ where $H()$ is a hash function, and $M$ is an (optional) and arbitary message string.

- Compute $ac+k \mod q$ (just as in the interactive protocol).

The upshot here is that the hash function is picking the challenge $c$ without any interaction with the Verifier. In principle, if the hash function is “strong enough” (meaning, it’s a random oracle) then the result is a completely non-interactive proof of knowledge of the value $a$ that the Prover can send to the Verifier. The proof of this is relatively straightforward.

The particularly neat thing about this protocol is that it isn’t just a proof of knowledge, it’s also a signature scheme. That is, if you put a message into the (optional) value $M$, you obtain a signature on $M$, which can only be produced by someone who knows the secret key $a$. The resulting protocol is called the Schnorr signature scheme, and it’s the basis of real-world protocols like EdDSA.

这个协议不仅仅是知识的证明,也是一种签名方案。

Phew.

Yes, this has been a long post and there’s probably a lot more to be said. Hopefully there will be more time for that in a third post — which should only take me another three years.

Notes:

- In this definition, it’s necessary that the statement be literally true.